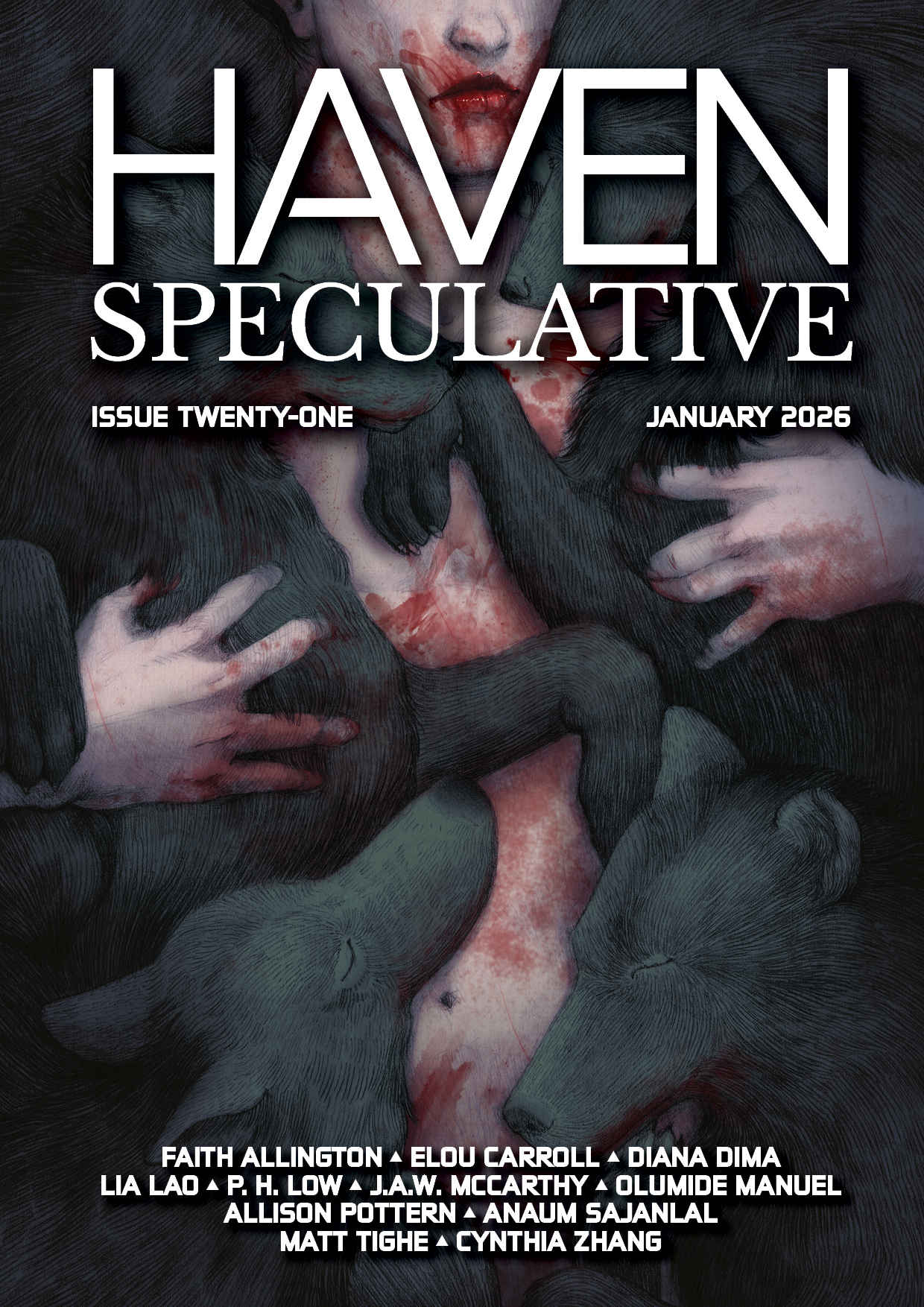

fiction

And If You Must Be Wicked, You Must

by Elou Carroll in Issue Twenty-One, January 2026

2177 words

You are looking right at her when it happens. When your hands clench around his throat—his skin bright and warm beneath your fingers.

It should be her with her nails sharp and her knuckles paling. She is behind him with her mouth hanging open. She cannot hold your stare—she looks away and bites her lip. For the first time, you are reversed, as if you were born in the mirror all along. She hunches her shoulders and squeezes her eyes shut.

Then, she looks up. She watches. She must.

#

He doesn’t mean to, the little boy with the gappy teeth and the tight ginger curls pressed flat against his head. And when you trip his eyes and mouth go wide; he turns away before you hit the ground.

You are four years old with a newly-skinned knee, your bottom lip caught between your teeth and your fists clenched—poised to kick and bite and scream—when they steal away your fight. One moment it’s there, the next gone like a breath unheld.

They bring her out by the scruff of her neck—a little girl made in the dark, the same shape and size as you. She, too, with her fists balled and her lip snagged between coaled teeth and a scrape on her knee in the exact same place as yours, hissing and spitting and clawing to be free. Your mouth and hands fall open and you try to walk to her—you’ve seen her before, in the night, in the dark, in your mirror when the lights are out.

“Look away,” your mother whispers, taking your shoulders into her soft hands and turning you gently to look at her, and not at the girl from the mirror. “If you must be wicked,” she says, “if you get angry, or so sad you want to scream and shout and everything else altogether, look away. You will never have to feel it again; she—it—will do it for you.”

And she did. And she does.

#

You are four years old and the two of you are playing clapping games. You giggle and laugh and sing the rhyme, and she grins along with you—you always wanted a little sister. When they catch you, they pull you away. Your bottom lip wobbles as you look up at them.

“But she’s my friend,” you whine.

They shake their heads. “No, Caris. It isn’t your friend.”

They teach you to ignore her, to keep her always at your back and pretend she isn’t there. That is the rule: if you must be wicked, if you feel wickedness bubbling up, look away.

When you try to be naughty, they hold your hands by your sides and tell you to stop. That’s what she’s here for. It is not for true people to be wicked. A wickend, they call her. The wickend will do it. You don’t need to speak to it, to look at it—it will just know.

And when she takes your wildness in her hands, their own wickends come out to punish her—it is not for true people to punish and be punished. They are so used to these shadowed reflections that they barely notice when their wickends push her squealing-silent to the floor.

You are seven years old and a shadowed hand tugs on your plaits. The boy he was made for—that same boy from before, his ginger curls loose now—giggles into his palm. He does not look away when his wickend pulls so hard that your neck snaps back. Your eyes fill up with tears and you squeeze her hand tight.

“Stop it,” you hiss through your teeth.

When he doesn’t, she tears her hand from yours and pushes the wickend so hard he rips some of the hair from your scalp. The boy looks away then, and you do too.

“Sorry,” he whispers as the un-teacher separates the wickends with a silent shout, the teacher-true hushing the both of you with a sugar-sweet smile.

Your wickend returns to your side with her lip between her teeth and blood dripping from her nose. From the corner of your eye, you see her mouth, And if you must be wicked…

But when you try to take her hand, she shifts away.

#

There are balloons and presents and party food, and everything is bright and warm. It is your birthday, and hers, but when you try to share your cake—pretty with lemon-yellow frosting—with your wickend, your mother takes it from your hands.

“No, Caris. No. You mustn’t.”

“Why?” you ask and the room falls silent. Even the wickends look at you, wide-eyed. The children that have them—those that are old enough to be naughty, to be angry, to be wild—hold their chins up high and do their best not to look at theirs, at yours, at each other. They fidget, one twiddles her hair, another bites his thumbnail, but they do not look.

Your mother moves you to the corner, as if it might stop them from staring—it doesn’t.

She takes your face in her hands and leans in close. “It just isn’t done, Caris. Stop this silliness.”

“But she—”

Your mother holds her finger to your lips.

Her wickend stands in the corner—she watches you, her eyes lit with interest. Your mother doesn’t look her way, not really. Instead, she just turns her head with practised precision until the wickend is in her peripheral vision. Your mother doesn’t know that you’ve seen them when she thinks you’re not looking—passing glances and sympathetic smiles. She presses her eyes closed and breathes in deep.

“No. Not she, Caris. Not she. It is not for birthdays or cakes. It is not a playmate, Caris. We’ve been through this. Come now,” your mother says and she leans her forehead on yours.

You try to wriggle away but she stays firm. “But you—”

“No, Caris, love.” She holds your hands and swings them to-and-fro, smiling brightly but it sits wrong on her face. “Let’s get back to the party. It’s not for us to be rude, love.”

As you follow her back to the table, you cannot meet your wickend’s eyes.

#

You are ten and you sit cross-legged in front of the mirror when you should be sleeping—you do not talk in the daylight anymore, do not hold her hand. You wait until it’s dark, until no one is looking—watching.

When you were younger, you asked her what her name was and she only shrugged.

“Sirac is my name backwards but that sounds silly.” You put your finger to your mouth and puckered up your lips like a fish, and she laughed. “It sounds like… Sarah! I’ll call you Sarah. There’s a girl called Sarah in my class and she has red hair and freckles and I think she’s very nice—like you.”

The newly-named Sarah shook her head but smiled too—she wasn’t supposed to be nice, even if she wanted to.

“Hello, Sarah,” you say and her face crumples.

Her pose echoes yours and she presses her hand against the glass. You meet it, palm-to-palm, knit your fingers with hers and pull her through. She falls into your lap and you hold her close as she sniffs and shows you the scuffs on her palms, the cut on her chin. She doesn’t talk out loud—they didn’t make her that way—but she doesn’t need to. You understand Sarah as you understand the steady thump of your heart in your chest.

You try not to feel wicked, try not to want to do naughty things but you are ten and you can’t help it.

You catalogue each blemish, take a tinted lip balm from the drawer and smear your own battle scars in the same places as hers. When you rub too far over, Sarah reaches out and guides your hand with shaking fingers.

Sometimes, she digs her nails in—but you don’t mind the hurt.

#

As you grow, you wonder: who of the two of you will pucker up their lips and kiss? Who of the two of you will be allowed to fall in love? They teach you that lust is a sin, so who of the two of you will bear children? You have always had questions—not just about boys and kissing—but wickends are not part of the curriculum.

“That is a home question, Caris,” your teacher said when you asked them. “At school, we concentrate on school work.”

At home, your mother looks at you and sighs and says in that breathy way of hers, “No, Caris. It is not for us to talk about these things.”

“Well, what is it for us to do, then? You always say that. It’s not for us this, Caris. It’s not for us that, Caris. But you never answer my questions.” You cross your arms and puff out your chest.

She doesn’t look at you when she says, “You shouldn’t ask them. You know the rule. You know what they’re for.”

“I’ve seen you. I’ve seen you talk to yours—the other mum—when you think I’m not paying attention.”

“Caris—”

“Why can you do it but I can’t?”

Your mother turns to you then and slams her hand down on the table. “Enough, Caris. Stop. I don’t want to talk about this again.”

And you don’t.

You are fifteen years old and not talking to your mother. You want to be wicked but you don’t know how. When you ask Sarah, she shakes her head.

But then you see him. The boy with the ginger hair is tall now, athletic. You look at his lips as he talks and wonder if they’re soft. This is wickedness you can work with.

He leans against the window as you walk up, playing with the rings on your fingers. He looks you up and down with that grin of his stretching his lips wide. Behind you, in the window, Sarah is shaking her head, hovering her hands over your shoulders. You roll your eyes at her and pretend she isn’t there until she takes hold of your wrist and tries to pull you away. You rip your hand from her grasp and she looks at her palm as if you’ve burned her. For the first time, you are glad she cannot talk, cannot cry, cannot call out, cannot shout at you to stop. You swallow, shake out your shoulders and walk on.

He greets you with open arms, he and his wickend and his grin.

You dance around each other after that, and Sarah refuses to look in your eyes.

#

You sit across the table from the ginger-haired boy, now man, and he is smiling. Polite, you smile back and resist checking your watch—Sarah does it for you. For what feels like an hour, neither of you has spoken, simply smiled passively at the other while next to you a war is waged and fought and won—shadow against shadow, teeth bared and claws drawn. When it is over, Sarah retreats through the mirror in the downstairs bathroom, shoulders shaking.

It has been this way for weeks; you come home and dinner is on the table. He waits as you sit, watches your eyes burn for a moment when you notice the ring box for the twenty-fourth day in a row and say nothing. Then you smile and you eat and you smile and you refill your glass and you smile and you clear the plates and neither one of you says a single thing. You are twenty-two and forever is a long way away.

“You’re not even going to open it, are you?” he asks, finally.

From the corner of your eye, you see Sarah slip back out of the mirror and wait. You do not know what to say to him so instead you look away, and you say nothing.

It is not the wickend that strikes you first.

And if you must be wicked. And if you must be wicked, you repeat beneath your breath. Sarah moves in front of you and bares her teeth.

“Are you just going to sit there?”

It is not the wickend that takes Sarah’s arms in his hands and shakes her and shoves her and kicks her when she’s down—the wickend only watches.

“Stop it!” you say and you grab at him but his wickend pulls you away.

When he is done, he walks away without looking at you. His wickend follows, shoulders back and head straight.

#

You are twenty-two and you are waiting. He has not been home since the previous evening but the ring box is open on the coffee table where he left it. He expects you to take it. Expects that it will be on your finger when he returns thick with drink, with that grin smeared across his mouth.

Sarah is next to you and for the first time in years, she is holding your hand. She looks you in the eye and mouths, And if you must be wicked… once more.

Instead of looking away, pretending that she doesn’t exist, you square your shoulders, lift your chin and say, “You must.”

© 2026 Elou Carroll

Elou Carroll

Elou Carroll writes spooky, whimsical, and strange stories. Her work appears or is forthcoming in The Deadlands, Baffling Magazine, FOUND #2, Flash Fiction Online, Cosmic Horror Monthly and others. When she’s not hoarding skeleton keys and whispering with ghosts, she can be found editing Crow & Cross Keys, publishing all things dark and lovely, and loitering on instagram (@keychilde), bsky (@keychild.bsky.social) and the website formerly known as twitter (@keychild). She keeps a catalogue of her weird little wordcreatures on www. eloucarroll.com.