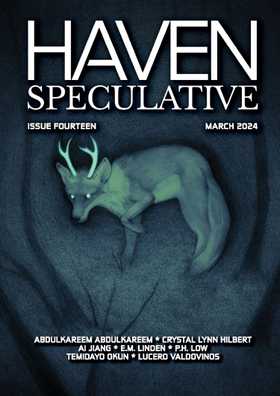

FICTION

A City Undying

by Ai Jiang in Issue Fourteen, March 2024

“I know you said you don’t like kids.” Lingwei doesn't look at me as she brings her half-smoked cigarette up to her lips, leaning against the half-broken fence I sit on top of. “But Aisha needs a sitter. Just for today. And I can't do it.”

Her hand wanders to her back pocket, feeling for her cig packet. She takes it out, shakes it—there can't be more than a handful remaining—and shoves it back in with a sigh. I can almost hear her lungs deteriorating in real time.

“Can't or don't want to?” I ask. “Where's Aisha?”

Lingwei shrugs and shuffles her feet, indifferent. Guilt and responsibility are things that have long since left most of us. “Dunno. She just said she needed some alone time.”

Strange. Aisha almost never strayed far from her son. Maybe there was little left of her melting brain and slowing heart. She had given everything to Mashaka both before and after the Great Rot. Her husband had disappeared that first night, after he’d gone to a local grocer to see if he could stock them up on food.

“What about Elu?” I ask, my lips dropping at the prospect of watching Mashaka for the day. The kid seems fine, albeit odd, always wandering around the city in search of a place where the vines will wrap around their bodies, whispering in a low voice about what I don’t care to know. There isn’t much I do anyhow during the day, like most people in the city, but I still don’t want to spend it following the kid around if I can help it.

Lingwei shakes her head. “She wandered somewhere to the other side of the city looking for unrotten food a few weeks back. Don’t you remember?” I do remember, but time has long escaped me here, and it feels as though I spoke to Elu just yesterday.

“Not sure why. Food much past expiry is perfectly fine for us to eat.” Lingwei coughs. I flinch.

The first time one of Lingwei’s lungs collapsed was two weeks into the Great Rot, which feels like a decade ago, though it’s only been a year. Rather than panic, Lingwei shook it off like a minor cold. I picture her remaining lung barely hanging on behind her ribcage’s protection, as though a single gentle breeze might make it crumble; I think the same about my eyes, the nerve endings hidden in each socket still attached, but the tether thinning with each passing day.

“Hey, Guangshi, so can you? Sit for Aisha, I mean?” Lingwei taps ashes onto the dusty ground.

I chew the inside of my cheek, then stop when a piece of me threatens to come loose. I avoid drinking water when I can, hoping it might slow the flaking of my chafed flesh that flutters down the tunnel of my esophagus with each slow swallow. The air was too dry before the Great Rot; now it’s too humid, though the humidity hasn’t helped my throat any.

“Fine,” I say.

Aisha and Mashaka appear, hand-in-hand, out of a nearby building, as though they had been waiting this entire time for my expected agreement.

I push myself off the bench, drawing up dust and sand where my feet land.

“You owe me one,” I say over my shoulder as I make my way to the mother-son duo.

Even though Lingwei’s next words were quiet and low, I still hear them: “There’s nothing left for me to give you.”

When I near the building, Aisha nudges Mashaka forward with a weak smile. “Thank you,” she whispers, her tone hoarse, a whistle through a voice box damaged with fractures and holes.

I shake my head and wonder if Aisha will return tonight, and if she doesn’t, then what?

With a vacant stare and smile, she drops her son’s hand and pats his head, as though she was looking through him rather than at him.

“My baby boy, my beautiful baby boy,” she hums, then drags her feet toward the other side of the city. It is not the heartfelt farewell I had seen in movies—the ones that end in waterfalls of tears, tight clutches, sobs into salt- and snot-stained shirts. It is not loud and dramatic, a wailing over certain loss. But perhaps sometimes a quiet sort of goodbye is much better.

We wait and watch until Aisha disappears, then Mashaka looks at me, eyes sparkling, not knowing that he will never see his mother again.

“Explore!” he says. And when I don’t answer, his smile wanes. “Can we, please?”

I force a tight grin. “Sure.”

Lingwei watches us with her last cigarette held loosely in one hand, as if contemplating whether to save it or to smoke it.

#

Even though his legs are only a third of mine, he runs too fast for me to catch up. I can hear the creaking of his bones echoing toward me from far ahead.

“Slow down!” I shout, to no avail. Even if he falls, there is no one left to miss him.

Mashaka was born only three years before the Great Rot, and we thought his youth might save him from it, or at least slow its process, but it has been consuming him faster than anyone else. Most of the children are gone now. It’s a miracle Mashaka is still here.

“Mashaka!” I try again.

I push my legs as fast as they can go, worried for the child as much as I try not to. In this city, it is a futile and unnecessary feeling. I cough and feel my own lungs quake in the hollow of my body and wonder just when they will collapse like Lingwei’s.

“Hurry, hurry!” Mashaka calls back to me, and I realize we are veering towards the other side of the city. I hope we don’t see Elu, and I hope harder that we don’t see Aisha.

Moss and leafy vines grow out from the cracked asphalt roads that Mashaka thuds across. I tread after him with careful, long strides. The greenery crawls up the sides of skyscrapers, sneaks through broken windows, settles across long abandoned houseware, and consumes the rot-engulfed people still inhabiting the buildings.

“Where are we going?” I ask, sucking in small breaths of cold air as I pant.

“Somewhere beautiful,” Mashaka says. I stop. The maturity of the tone, though still holding the whimsical and wondrous curiosity of a child, shocks me, as does his ability to look at this ruined, dying city and call it something usually reserved for the opposite—glistening waterfalls, burning sunsets, lush forests. I look at Mashaka, really look at him for the first time. And I suppose, like his mother, he is beautiful too, with the optimism and innocence I wish I still had.

Mashaka ducks suddenly into a building a few paces ahead, peeking his head out as though worried I might lose him. This might have been an issue without the Great Rot, when there were still large city crowds. But I would not have known Mashaka then because I would not have met Aisha. Or Elu. But I knew Lingwei before. She used to be more like Mashaka, but now she’s more like me. I sometimes wonder if she regrets our friendship. I can never tell if she is like this now because of the Great Rot or because of me and my pessimism.

When I reach Mashaka, he raises a finger to his lips and whispers, “Do you hear that?”

I shake my head. “Hear what?”

They say children can see ghosts. Creatures not of this world. They also say children know the good from the bad. And sometimes I wonder if Mashaka’s senses for this aren’t accurate because he always runs straight toward trouble rather than away.

“Elu,” Mashaka says, his voice a curdling rasp.

I shiver and feel my spine shake, my muscles threatening to sever in sections like a ribbed, boned worm—sliced. My breathing becomes erratic, jostling my body, the joints that keep my legs and arms together threatening to disconnect and leave me in an immobile heap on the ground.

“Where?” I whisper, my voice fear-tinged and emotional—feelings I thought I had left behind a few weeks into the Great Rot. I feel a sense of hope we might find my friend, that she is still alive. But this feeling is selfish, because to live now is to suffer.

Mashaka points but the smile doesn’t stray from his face for long. “There! Elu!”

I follow his finger to a dead body no longer resembling Elu. The only sign that it is her is three missing teeth: two on the top and one on the bottom row. She’d lost them a few months into the Great Rot while trying to chew through the core of a rotten apple.

“She says she’s happy. She says she’s home!” He points more frantically now, his flower-speckled dreads bouncing as he hops from one foot to the other. There is the sound of crunching bones each time he lands.

“Home…?” I ask. I want to reach out to stop him before his head flies off. It wouldn’t be the first time something like that has happened here. It is common in children at the height of their excitement, anger, or sorrow. Aisha is much better at keeping Mashaka calm. I just hope I don’t return with only half of the boy.

“She says she’s comfortable in her embrace. Mother’s.”

“Mother?” I bend to meet Mashaka’s eyes and place a careful hand on his shoulder, hoping it stops his fidgety movements. And it does. “She’s with your mother?”

Mashaka looks at me, confusion drawing his brows low, and offers a questioning tilt of his head, as though I should already know the answer. He points to the leaves and vines and damp soil covering Elu’s skeleton. “Mother.”

He shakes off my hand and walks to the remains, where he crouches to lift a single curled vine for me to see. As soon as he notices my focused attention, he places it gently back down, as though it is as delicate as porcelain, as breakable as a newborn child. “Do you understand?”

I stare hard at Elu’s stark white bones and the vines and greenery that slither through her ribcage and out of her eye sockets, stare at its caressing leaves and the plump petals of its budding flowers. And for the first time, I don’t see death in front of me, but life. That is when I hear the whisper.

Child…

It is an echoless voice that should feel like danger but is instead as warm and gentle as a faint caress.

Return to me...

A single vine frees itself from Elu’s skeleton and slides across the cracked flooring, then wraps around my ankle—not in a choking hold, but a comforting embrace.

Mother—the one who has been waiting for us to pass true rot. Mother—who has been lying, trampled under our paved roads, our smoking factories, our dead homes. Mother—who always knew that the true Great Rot is the civilization we have created, the one that shuns her, the evolution we believe superior. Mother. And she has returned to reclaim us all. Elu. Aisha. Even Mashaka. An innocent, beckoning voice we refused to listen to for far too long.

I look down at my hands, the dead skin rubbing off to show pink and red muscle underneath, the thin veins still pulsing with blood.

Child...

“Mother,” Mashaka whispers. A vine snakes its way towards his feet, then crawls up his leg, clutching at his knees, prodding his thighs. His limp arms welcome the vines that detached from the surrounding walls to embrace him, lace around his fingers like a gentle handhold.

And this time, I listen.

With careful steps, I join Mashaka next to Elu’s body. Several other vines reach out to cover my dying skin, engulfing it as though I have always been a part of them, returning just now, after being apart for too long. It wraps around my neck, pokes into my ears, scrapping against my eardrums. Next to me, Mashaka has become almost entirely consumed by the greenery. His timid yet reassuring smile is the only thing peeking through, the rest an entanglement of woven vines and leaves.

I only pray that without Mashaka’s voice, Lingwei may still find her way to us and let go of the death we have so long believed to be life—sometimes, what we believe as loss may well be the hope we are seeking, and what we desperately cling onto as hope may in fact be the destruction of us all. We need to let go of what we once believed when the world has shown us how wrong we were all along—we are not rotting, we are returning the world to its glory; we are not a dying city, but a city undying.

© 2024 Ai Jiang

Ai Jiang

Ai Jiang is a Chinese-Canadian writer, Ignyte Award winner, Nebula-, Locus-, Bram Stoker-, and BFSA Award finalist, and an immigrant from Fujian currently residing in Toronto, Ontario. She is a member of HWA and SFWA. Her work can be found in F&SF, The Dark, Uncanny, among others. She is the recipient of Odyssey Workshop's 2022 Fresh Voices Scholarship and the author of Linghun and I AM AI. Find her on X (@AiJiang_), Insta (@ai.jian.g), and online (http://aijiang.ca).