Fiction

Magical Girl: Corporate Failure

by Lia Lao in Issue Twenty-One, January 2026

The problem with saving the world at sixteen is that you’re doomed to chase that high for the rest of your life. You’ll fall asleep tossing and turning, dreaming of tiaras that cleave through bone, sky-high heels you can land spinning kicks in, and blood splattering across your face—thick, black, and pungent, like decay settling into your skin.

And when you wake each morning to the tinny, lifeless pulse of your alarm, you’ll wish that your limbs actually ached, that the claw marks across your ribs were real. Because at least then you would feel something. “Saving humanity from the... Continue →

Demon in Repose

by J. A. W. McCarthy in Issue Twenty-One, January 2026

You know this elevator well.

You’re leaving the room that was never really your room, another transient visitor in a transient space, but something nips at the back of your neck as you wait for the cables to pull the elevator car up to your floor. What did you forget? Blue and grey and beige carpet squares point endless forking paths towards doors sheltering lost things and lost people, but you’re not among them anymore.

Last night’s haven has spat you out despite its warm welcome. What did you leave behind and can you live without it?

If you go back to that room,... Continue →

Branches

by Matt Tighe in Issue Twenty-One, January 2026

You smile when you see her across the street again.

She laughs when you ask her the way to the station. It is right there behind her, South Entrance in huge letters, people bustling in and out of the oversized doorway.

She asks where you are from—don't they have trains there—and you smile and shrug. A version of you exists in almost every branch of reality, but part of you, the part that hurts, that knows how she holds your heart, has only just arrived in this world.

She apologises, stumbling over the words. She does not usually tease people, she says.... Continue →

Bootcut

by Allison Pottern in Issue Twenty-One, January 2026

Running your hand along the clothing rack, your finger catches on a Goodwill miracle: a pair of jeans that actually fits. They have no tag—no name brand—just a questionable stain below the left front pocket, no big deal. It’s like maybe these jeans have lived a more exciting life than you have. Maybe if you put them on, a bit of that excitement could rub off on you.

The flared, dark-washed jeans look like once upon a time they were very expensive. Now that they’re in your broke hands, they’re merely “vintage.” But in the claustrophobic changing room mirror, they make your... Continue →

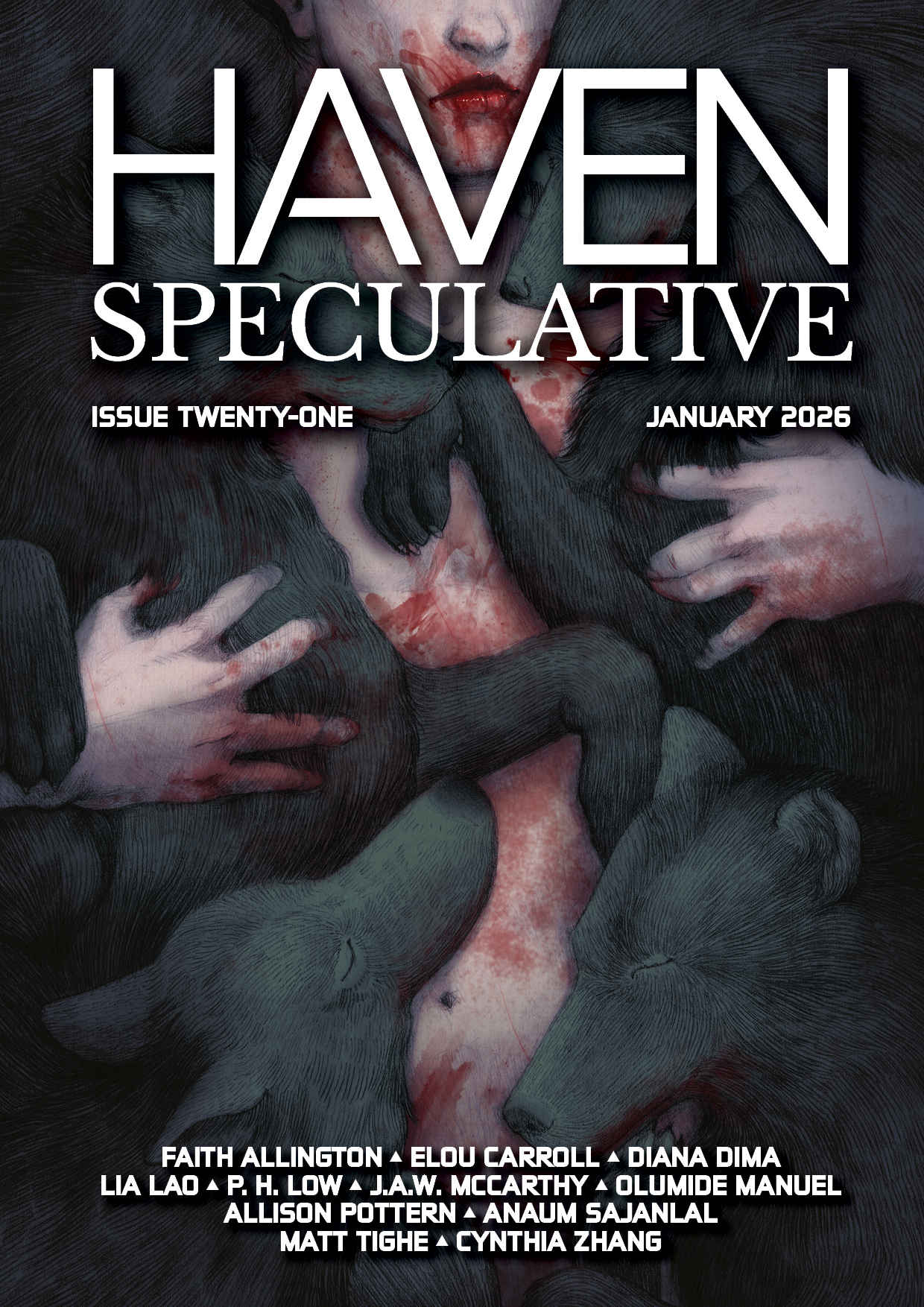

And If You Must Be Wicked, You Must

by Elou Carroll in Issue Twenty-One, January 2026

You are looking right at her when it happens. When your hands clench around his throat—his skin bright and warm beneath your fingers.

It should be her with her nails sharp and her knuckles paling. She is behind him with her mouth hanging open. She cannot hold your stare—she looks away and bites her lip. For the first time, you are reversed, as if you were born in the mirror all along. She hunches her shoulders and squeezes her eyes shut.

Then, she looks up. She watches. She must.

#

He doesn’t mean to, the... Continue →