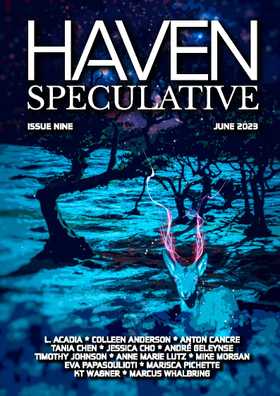

FICTION

A Deep and Breathing Forest

by Anne Marie Lutz in Issue Nine, June 2023

After I retired I wrapped up my affairs as best I could and headed back to the section of woodland in the mountains that had caused me so much trouble years before.

I’m not going to say it “haunted” me — I wasn’t the kind of person to let a snafu like that ruin my life. But I thought about it often, how it had confounded all our efforts, how the old woman had guarded access to that forested patch with cunning and ferocity. Her opponents were young, smart, money-hungry. Developers, investors, politicians, people with expensive degrees and technology at their disposal. The modern world, in fact.

Like any sensible person would, I still wanted to know what had happened. The forest had proved invisible to our tech, impervious to our analysis. The 2008 recession derailed the developers’ plans, and a mysterious conservation buyer snapped up the forest while the developer was in trouble.

They had a little potluck for me at the office, gave me a plaque with some words about my years of service for the engineering division. When I nodded my way out the door I didn’t expect to see any of them again.

I headed west to the old woman’s house in the forests of southwestern Pennsylvania.

Her house wasn’t much to look at. A tiny meadow next to the house gave way to a curtain of green that hid the interior of the woods from view. There was poison ivy wrapped around tree trunks, some kind of thornbush that could draw blood, and rocks that rolled underfoot when people tried to enter. I caught a glimpse beyond, of huge old trees, vines, and a carpet of moss and decomposing leaves. But only for a few feet — then it grew impenetrable.

I wanted in there so badly I could taste it. It tasted like mushrooms, maybe a little sharp like pine, and dark like a forest on a moonless night.

I didn’t understand any of this, but there it was.

It took five minutes for Clara to answer my knock. She was shorter than I remembered, hunched over with age, and her hands gripped a walker. Her eyes were still clear and brown as the earth and the trees she protected. There was a streak of green in her hair — it didn’t look like hair color but more like moss.

“You. I remember you. Lincoln, wasn’t it? I thought you’d show up someday,” she said. “Do you want to come in or should I come out?”

“Out, ma’am,” I said. “If you can.”

“Of course I can.” She pushed open the door and maneuvered out onto her sagging porch. “Tell me why you’re here.”

“I need to know,” I said, then stopped and spread my hands in apology. I hadn’t meant to be rude. “I’ve retired. I’m ready to let everything go. But I need to know how you did it.”

Clara shook her head, a slight motion that was more than a No, more like a comment on my presumption. I thought she was about to turn me away. I couldn’t bear it if she did.

A moist current of air from the forest drifted by. I breathed it in, then coughed until I was bent over, helpless to stop the attack. When I could finally draw a full breath again, I stood up, weak and sweating.

Clara frowned. “You’re ill.”

“It’s cancer.” Such a blunt sentence to summarize that shattering diagnosis. I’d struggled to go on as I always had, focused on the numbers, the treatment plans, statistics. But it hadn’t worked.

“And this cancer made you want to come here again, after so many years. Why?”

No ‘I’m sorry’ from her. I liked that.

“I’ve always puzzled over it. I want to see what’s in there, why we could never complete a survey. Why even the satellites couldn’t see anything in there, even when the leaves fell.”

It had never made sense to me. You could measure anything. That was the basis of all science, wasn’t it?

Clara laughed. “You’re not going to find any of that out.”

I hoped she wasn’t right. I wanted to know what happened to the young engineer who’d managed to walk a few yards into the forested tract. She’d gotten lost, and something had happened to her, though coworkers watching from the meadow swore she’d been in sight the entire time. She’d never returned to work. Lived alone somewhere in the desert now.

The developers had poured a lot of money into the fight for this land, until the conservancy had bought the whole thing. Not that anyone owned this place — standing there breathing the exhalations of the forest, I knew that.

“I’ve been dreaming about this place every night.” Saying it out loud felt like a confession. I felt freer, too, as if I’d taken off my business suit and wore only my skin now to face a different, older world. My dreams had been about pinpricks of moisture on my skin, toes digging into soft soil, inaudible music that might have been the sap moving beneath the skin of the younger trees. I didn’t pretend to understand it.

“Why did you fight so hard?” I asked her.

“This place is special. When it goes …” She opened her hands as if letting something go. “The world will change.”

I lowered my voice to a whisper. “What is it? Is it magic? Here in western Pennsylvania? Why here?”

“Why anywhere?”

“Has it always been here? Does it … move?” I’d looked up the old places. The Bialowieża Forest, the Daintree Rainforest, ancient sites in the Amazon and Africa. This place here had no name except for its designation on legal documents. I didn’t believe it, couldn’t believe it … and yet.

“How long have you been here?” I asked Clara.

Something cracked in the forest and echoed around the little glade where Clara’s house stood. I jumped. A fallen branch? It had sounded like a shot. My arm stung as if I had been stabbed.

“You need to let all that go.” Clara seemed taller now. She wasn’t holding on to her walker anymore, and the backs of her hands looked faintly green.

“But you can trust me, ma’am. I promise I won’t tell anyone else.”

Another sharp crack, followed by a low groan from the forest.

A shiver ran through me. I’d done something wrong. Dangerous. Too many questions? Too much analysis, like the people who’d tried to use technology to map this place, tried to analyze the geology and the drainage.

My arm was bleeding now. I looked at the thin trickle of blood. Surprisingly, it didn’t bother me much at all.

“Lincoln.” She sounded stern, saying my name like that. The green flowed up her arm, shading her skin like fresh spring leaves.

I caught my breath in wonder, then coughed again.

“You didn’t come here dying from cancer to find a scientific explanation,” Clara said.

I shook my head at her, but the pain in my chest told me to listen. She was right.

I handed her my cell phone. I’d turned it off a while ago, but it felt heavy and dead on me, and I wanted it gone. I looked at my car, pulled over at the wide spot in the gravel road, loaded with my overnight bag. I had reservations at a hotel further west, and an appointment to meet with another doctor in Chicago next week. I’d had plans. They seemed faint and unimportant now.

I let it go. All I wanted now was what I’d been dreaming about. I took a deep breath of the air, heavy with organic fragrance, and felt as if I’d freed myself from something.

Something exhaled all around me, a sigh almost. Something knew I had reached a decision.

I moved off the porch, back into the little field that fronted Clara’s house, and stared towards the forest. Bottlebrush grass and wild rye edged the field, butting up against the formidable outer boundary of the forest, but then gave way to spiny thistles. The bushes that guarded the gaps between the poison-ivy-wrapped trees were armed with thorns like claws. I saw no way in.

I heard the distinctive bang of a screen door. I turned to see if Clara had gone back inside but there was only more green. Leaves brushed my face, so close I had to move them away from my eyes. Tiny white flowers like delicate fireworks touched my shoe, as if I’d stood here forever.

I hadn’t walked into the forest after all. It had surrounded me.

A deep silence reverberated in my ears. It was calming, like something I might have heard before I was born. Water trickled by my feet, pinpricks of light like molecular fairies drifting along its surface. Goosebumps raised on my arm — something had touched me.

I tried to remember. Who had I just been speaking to? There had been someone, a guide maybe, or a guardian — someone important.

I never moved, but somehow I was deeper in the forest, standing before a little hollow of knobby tree roots snaking into the earth. I lowered myself between them, sinking and expanding at the same time, until my hands caught in the rich soil at the base of the tree, a thing that seemed right and as it should be. I was content to breathe, pain-free, even as I began to change.

I tilted my head back to watch the night follow day follow night, an endless progression of sun and cloud and moonlight and deepest black above the heads of the tallest trees. The stars sang, a sound that joined the deep calming silence of the earth that surrounded me.

Something was howling nearby. Something that was getting closer. Warmed by the ancient tree, part of this living place, I didn’t know or care what it could be. But I thought I would soon. After all, it was calling to me.

© 2023 Anne Marie Lutz

Anne Marie Lutz

Anne Marie Lutz is the author of three fantasy novels. Her Color Mage novels were re-issued in 2019 as Black Tide and Sword of Jashan. Her newest novel, Taylenor, was released in 2019. She has also written several short stories, appearing most recently in the Blood on the Blade sword & sorcery anthology, the Dark Recesses Press webzine, and the Sleepless Decompositions podcast. For more about Anne Marie’s work, you can check out her blog at annemariesblog.wordpress.com.