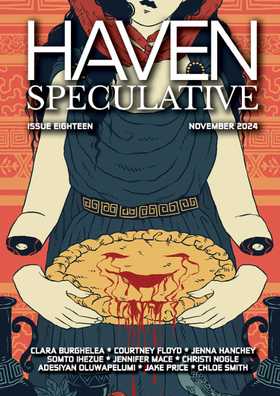

FICTION

A Eulogy for Patience

by Chloe Smith in Issue Eighteen, November 2024

5198 words

"This can't be what you want," the oldest and most powerful suitor says. His mouth is stained red. He wipes it with the back of his hand, jerks his head towards the chaos that breaks across the room, the shouts and wild gestures, the spilled wine and half-eaten food.

"They will beggar you with this waste. Is this a proper legacy for your husband's riches?" His words are soft, but his grin curves like a scorpion's tail.

I refuse to look. I keep my spine stiff and tilt my chin down to stare into the leaping flames in the hearth.

He leans closer. I can smell the wine on his breath. It was a good harvest, transformed now into sour vapors and grasping hands. I draw mine farther away.

"You must choose one of us," he says. "Choose while you still can." There is a crash behind him, answered by hoots of laughter. He continues, "While you still have goods of value left."

The wine makes him transparent. As if I had any doubt.

I take a slow sip from my own cup and force my eyes to meet his. I smile demurely at him. Sadly.

"If only I could heed your wise advice, dear friend. Truly, I understand its urgency." As if any but a fool would not. "But my sacred duties yet forbid me to act. If I accept, as you ask me to, that my husband is truly," I almost choke on the word, "dead, then I must honor his passing before I consider taking another lord. I need time to prepare and write his eulogy." I draw myself up and away. I hold my duty as a cloak of inviolability.

I think it may not be enough, that he will dispense with this veil of courtesy and simply take what he wants. But I forget: my status is part of what he covets. The honor of a loyal widow, of one of the oldest houses on this island, is too great a prize to be destroyed in the taking.

"Of course, dear lady. You inspire us all with your devotion." He drains his cup and holds it out again. "But you cannot refuse a man a sop for his disappointment."

#

The guests carouse far into the night. They drink and eat, sing and boast and argue. They vomit in corners and tease the old dog, throwing bones at his head where he lies before the hearth fire, laughing when he snaps and cringes away.

The serving girl knows not to cringe, not to snap like the dog when they pull on her elbow or her waist, when their hands threaten to tip the pitcher in her grip or trace the shape of her body beneath its covering shift. She's mastered the art of the teasing smile, the flattered laugh. It's easier that way, safer. She's learned the hard way, from pinched skin and harsh words, from the cuts and bruises she washed in the salt tides of the sea. She saw a fellow servant knocked to the floor with a drunken fist for resisting the guests' advances. That girl is her sister in all but blood. They have carded the same wool and scrubbed the same pots, together under the absent lord's roof for all the years of their young lives. Now her sister crouches in the kitchen, nursing an ill-set, aching shoulder and turning the roasting spit, a crone before her time.

This girl will not let herself be destroyed like that. Her body is all she can claim in this world. She cannot let it be broken, so she must let it be used.

That is what she tells herself, at least, when she follows the beckoning guest into the shadows beyond the great hall. He is young among the suitors, his appetites unregulated, even by their standards. She tries to be soft, to let his urgency spend itself without tearing her apart. He gasps and laughs, breath hot and sour on the back of her neck. Then he stumbles back into the light and merriment of the hall. She turns and watches him recede as she pulls down her skirts. Around his silhouette, the glow of firelight flickers, fuel in the hearth piled high, even at this hour.

She wishes the fire would rise up and burn this whole great house. She hopes the heat of her anger, banked inside her, will burn away whatever seed he left in her belly.

At last the house quiets. Some of the guests depart for the night, while others have drunk themselves insensate. They lie on the floor of the hall. The servant girl tries to clean the spaces around them.

#

In my chamber late at night, I sit at my writing desk, a single lamp wavering.

I spread a fresh sheet of papyrus in front of me. My pen is sharp, its tip black with ink.

I cannot bear to write this eulogy yet.

Instead, I write myself a story. The story of my heart's hope.

My husband returns, alive and vigorous. The gods of sky and sea smile on him. He throws off the ragged robe of travel (a disguise, no doubt—he was always enamored of subterfuge, making his plans more complex than they needed to be) and stands tall in the heart of our home. He calls loyal men to his side, and they fight like heroes out of legend. They decimate the vulgar interlopers who have aspired to take his place. They kill the poor fools who fed and served the suitors without question. He restakes his claim to lordship—and then he turns to me.

"But why did you hide your face for so long, my lord?" I ask. "I would have welcomed you with open arms from the moment you first set foot on our island."

"How else could I have defeated these miscreants?" He jerks a head at the carnage staining our home. "It is through my great cleverness that I have returned a victor."

I smile. It is his vanity, but so characteristic, so familiar, that it breeds tenderness.

He adds, "And how else could I be assured that you had remained loyal?"

The smile fades from my face. I scratch the reed pen across the words, drowning them in wasted ink. Even as I dream the best of all possible endings, I cannot but imagine the mistrust. My reason—remembering my husband's nature, even through the rosy haze of nostalgia—warns me that will come too, should he return.

#

The next day, the feasting continues. The servant girl runs the gauntlet of the hall. She goes from the kitchen to the storeroom and back again. The lady of the house meets her on the way, and the girl ducks her head, clutching a heavy amphora in her arms like an infant. She thinks the widow must see the resentment in her eyes.

"How are our stores?" the lady asks.

Raided. "Wanting." The widow must know both answers. She is in the hall every night, watching the feasting. How could she not anticipate the empty shelves, the jars of oil so light a child could shift them?

The girl stifles the emotion that hums through her limbs with all the energy of divine lightning. What selfishness for the mistress to resist, to prolong all their suffering.

#

As the evening lengthens, I say I must return to my writing. The eulogy is not yet done.

This time, though, when I hold my pen over a new page, what emerges is the story of my heart's bitterness.

My husband is delayed. Beautiful women—witches, goddesses, and princesses—are overcome by his charms. He dallies with them, seduced and seducing. The ties of love and duty that draw him home grow thin as spider silk, out of sight and out of mind. Amorous adventures are no stain on a hero's journey. They are to be expected. He may love these others, yet leave them and walk away unchanged.

I cross the words out with such urgency that I break the nib. I spend the rest of the time before I sleep carving new reeds. Each flake that drops away beneath my careful knife is a tear I will not shed. I refuse to weep at the unfairness of the world.

#

The serving girl sleeps curled around her sister's back, the two of them like stacked shells on their narrow pallet. Her sister shifts, moans when splintered bone pains her. It wakes the girl in the steely light before dawn. The kitchen fire has grown cold, its cinders faded to flaky white ash. She kindles it anew and then goes out to the well.

The swineherd joins her there. He has blood beneath his nails, and he smells of pig shit, even this early in the morning. She pours out her first urnful of water for him. He shakes out his wet hair, droplets flying out around them both, catching in the rising light.

"Who do you want her to choose?" he asks.

"What does it matter?" She replies. She has seen the measure of these men and knows them all to be wanting. "They are all pigs."

The swineherd inclines his head, not quite conceding her point. "Pigs know where their best interests lie, at least. Do you want to know what I think?"

He clearly wants to tell her.

"The oldest one is clever," he says, voice warming. "He's watching the others, watching the mistress. He's waiting for her to run out of patience with their feasts and fucks. A man like that, who can run the animals before him in a herd, let them clear a path for him—I respect that."

Is that why you butcher for him and the others, night after night? She wants to ask. Why you thin your drove of pigs without thought for the future? She can't fault him, though. They all offer up flesh, in one way or another, bribing gods or men to let them live another day, to hold onto hope. He wouldn't want the new lord of the house to remember the swineherd as one who scrimped and shorted the feasters, as one who ever begrudged the new master's presence.

She lifts the sloshing urn to her hip. "I don't trust anyone who treats his companions as animals to be used."

#

The next night, the men seated along the tables clamor in chorus, deafening me: "Choose! Choose! Choose!"

They beat their hands faster and faster, until the rhythm breaks into cacophony, and one man falls from his seat, overcome with hilarity and wine. They do not quiet until I stand and repeat my promise and my excuses—decision, eulogy, duty, patience. Their silence, as they all weigh my words, becomes oppressive as their endless noise. Their eyes on me are hopeful, speculative, greedy—except for the oldest and most powerful. He glares, angry that I have shared this promise he thought reserved for him.

My lies grow dangerous. I must watch him. But what good will watching do?

I retreat to my room to write the story of my heart's prayer.

From the gold-and-ivory halls of the celestial palace, the gods look down and see my virtues. They see my overabundance of patience, through all the years of my non-widowhood: alone, but without a widow's autonomy; caretaker, but not mistress of her husband's house. The gods deign to touch my life, as—the stories go—they often do for heroes. They reward the hospitality I have poured out like lifeblood beneath a butcher's knife.

A footstep in the doorway. I look up, my breath catching with unreasonable hope. Some god has stepped from the poets' tales and into the confines of this household to offer me deliverance.

But no, it is the hard-eyed serving girl. She holds yet another cup of wine.

"He sent it up to you with his regards," she says, "before he left for the night."

She doesn't need to tell me who he is. In the privacy of my chamber, my tongue breaks free. "How generous," I say, "to offer me yet another cup of my own wine. Not all the wine I could have saved if he and his fellows simply respected my wishes and went away." Nevertheless, I reach for the cup.

The surface of the liquid shivers as the girl holds it out, like ocean waves lifting with the sea god's wrath. Her own words escape her lips' boundary, then, harsh and truthful. "They would all leave, if you would only choose one. If you would let go of all this—" Her gesture takes in the crumpled, ink-stained papyrus sheets littering the floor, the bed I've kept cold for twenty years. Wine sloshes down like an offering, and I snatch the cup from her trembling hands.

"How can I let go?" I ask her. "How can I choose among the many heads of this monster? And why should I? They call me widow, but how do they know? The only surety is to wait." I look back at the unfinished writing on my table. "I've prayed for better choices, for the gods to reshape my fate."

"Prayed for better fate." The girl's voice cracks. She spits out a sound that might be a laugh or a sob. "Don't flatter yourself. That's not for you. That's for heroes, for kings. Maybe for maidens. There are no good choices for us."

She swallows, stills her shaking. I can see the effort it takes to reel herself back in, careful as winding new-spun thread.

She is right, though. Have the gods ever helped one such as I? Would they even know how? I am not a warrior in battle, to be protected by divine wind or cloaking fog from the spear of an enemy. Seasons have passed, and nothing has changed.

I feel tears start behind my own eyes. "It seems such cruelty that the gods would trap me, would ask this sacrifice of me, after all these years of loyal devotion."

Now the look she turns on me is pure scorn. "Do you think we have not already sacrificed? The security of this house and the people in it, our bodies and our goods—and all you've been able to protect are your flesh and your honor. I don't wonder if the gods are cruel."

She is right again, and I can't look her in the eye to admit it. "Thank you for bringing the wine. You should go to your rest now."

After she leaves, I look down at the paper bearing my heart's prayer, the one that will remain unanswered. Then I feed it to the flame of the lamp. It is not an offering.

In my wide and lonely bed, I dare to imagine a different ending to my story.

I release the long-held dream of my husband. I leave my home under cover of night.

Alone beyond the walls of the house, I make my way to the shore of this island, the only land I've ever known. I find a boat that will bear me away, out of this story, beyond the knowledge of the gods. I lift an oar, ready to steer myself. Towards life or death, it will not matter. My path will be my own, and I will wait for no one anymore.

My eyes open on the darkness. I sit up.

#

The serving girl banks the hearth fire in the great hall, shadows thick and heavy all around her, emotions dark and obscure beneath her breast. She misses the pure anger she felt towards the widow, the resentment of a woman who won't do what's needful. That anger is still there, but now she must also carry the memory of the lady's pain, her talk of traps and sacrifice. The girl hates such self-pity, but she understands. She knows too well what a trap feels like. If she had the power to resist its tightening grip, wouldn't she do the same?

Still, when she catches sight of the lady's slender form masked by a heavy traveling cloak among the shadows, rage burns away her sympathy. So she will run and leave her suitors to scavenge this house like wolves.

The serving girl feels the weight of the future, of the destruction and desecration to come. Her strength, so carefully husbanded for so long, falters and she sinks to her knees before the banked coals. She catches her weight on her hands.

She tries to imagine running like the widow—but where would she go on this tiny land bounded by the god-ruled sea? She claws her fingertips into the cold, old ashes. Could she rake them down the face of the next man who reaches for her? Would it do any good? She wants to howl.

This is the fate the gods have brought her: pain and more pain behind every choice she has. She raises her hands to her face, smears the hearth ash across her forehead and cheeks. She might as well mourn the coming losses as try to fight them.

Heat flares, then. It burns from the ashes on her face and hands, flows along her limbs and kindles at her heart. She reels as the hearth fire flares inside her skin, a rush of power like nothing she's ever felt before. She's almost lost within it.

#

I get as far as the outer threshold before a voice calls me back, tangling my limbs and the air in my lungs. I freeze with the door still open behind me.

Mortals are damned if they look back, but I cannot help myself. I peer across the courtyard and into the hall beyond. The voice was a thunderclap, and I look for any sign of movement, men jolted from besotted sleep to witness my failed escape.

I hear the voice again, and I realize it is no more than a whisper, a breath against my cheek.

In the shadowed hall, among the insensate forms, flames flicker. A woman stands at the hearth, firelight glowing against her hair. The sight pulls me back, unwilling.

It is the serving girl, standing taller, prouder than I have ever seen her. But also, it is someone else, a woman whose hair hangs long and thick and dark as wildfire smoke, whose eyes sear me. My legs weaken, and I sink down in obeisance. She looks away, reaching out and into the column of heat above the flames. They leap up around her hand.

"You would let your hearth grow cold." Her voice holds the crackle of the cookfire and the laughter of family. It is stern authority and comforting warmth. It is home, lost and longed for, the hope of a child and the regret of old men. It brings me to tears.

"This is no hearth of mine," I tell her through my choked throat. "I do not hold it, except by men's forbearance, and now that burns away faster than summer-dried hay."

"And yet you have held it for twenty years," she answers. "Not your lost husband, the man whose very shadow has faded from this room. You have kept the fire alight, gathered the lives around it—servants, herders, elders and children. You leave them now to cold ashes, to men who will fight for its gold and flesh and tear the remnants apart between them."

Rage cracks my heart open. It pours out the bitterness of this long, lonely time. "And what choice did your siblings give me? All my paths run to emptiness and ruin in the end."

She looks at me directly once more. Her face, that of the girl whose form she rides, is like a mask. I once saw an ancient, lightning-blasted tree ablaze within the unchanged cloaking of its bark. Her eyes have the light of that inferno.

"I tell no stories," she says, "and none are told of me. I do not promise intervention or retribution. But I will die with these ashes. The path you've chosen promises that."

She gestures widely and the fire flares up again, illuminating the sleeping bodies, the dirt and broken furniture. It shines into the rooms of the servants and retainers, the very young and the very old. Their sleep is only a brief respite from straining to see which way the coming ax will fall.

I close my eyes against the brightness, against the shame. "I cannot spin a story of my victory." My voice is a reedy whisper.

Hers is even lower, thrumming in my bones. "Protect the hearth. Make that your story." Then she is gone. The fire sinks back to a soft glow. The serving girl sways and almost topples into it—except I catch her and wrap my arms around her. She buries her head in my shoulder, muffling her sobs.

A sleeping man snorts and turns over.

#

The next evening, I wait in my chamber as the noise in the hall swells like an abscess. The servants have emptied the wine stores on my orders, and the swineherd has butchered another suckling pig—although after he is done, I order him to take the sows upcountry to the forested hills, to sleep there as they forage. He is young and foolish. Better he be out of harm's way. I confer with the serving girl one more time. I see my desperate intention mirrored in her eyes.

After the pig is stripped of flesh and the guests have grown wobbly and hard-headed with drink, I descend to the hall. I have put on my richest necklace, strands of heavy gold and glimmering mother-of-pearl. I wear my old bride's dress. The rich purple of its dye, traded at my father's expense from distant Chyria, has not dimmed with all these years. I think of the hope I felt then, the uncomplicated joy, but those feelings are faint, as faded as the face of my husband in my mind's eye. These things will not come again.

The feasting men go wide eyed when they see me. I stop before them, let them take in the implications of my finery, watch as their mouths slacken. I let my gaze travel down the sides of the hall, over the hanging weapons, prizes won by my husband's family long ago—spears and swords and heavy ax heads.

"I have completed my work," I tell them and unroll the papyrus sheet I carry. "I shall honor my husband's memory fully with this reading." I find the predator smile of the oldest suitor at the back of the crowd. I am sure to look directly at him as I say, "And then I shall choose his worthy successor."

They note the direction of my gaze. Some faces crease with disappointment or with frustration, while others, those seated nearest him, smile in reluctant admiration. Some even reach out to clap him on the back. Factions have formed among the men in the crowd.

Still, my nerves sing as I swallow, look down at what I've written, wait for the rustles of anticipation to subside. Then I begin to read.

"You all remember my husband as a great man. Stories of his clever wits and of the glories he won in battle persist long after his flesh become shadow. He needs no eulogy for his greatness to live on. I speak instead of the space he left behind. An old house, its roots hardy and deep as olive trees, its people loyal and resilient. We remain, and it is our hearth now, our labors that have kept it..."

#

The servant girl has worked hard to keep the cups filled tonight, bestowing smiles, suffering the touches and lingering eyes. She comes back again and again to the one who had pushed her into the shadows before. She saves her most winning glances for him, leans over and breathes into his ear that she thinks he is the finest one there, that she doesn't understand what the lady of the house is thinking not to choose him in a heartbeat. He laughs and squeezes and gulps his wine, earning applause from his tablemates. His appetite stands out even among this company.

The servant girl moves carefully but quickly as the tenor in the room grows ever more raucous. She must seem to be everywhere at once, so that no one will notice the lack of other servants, the old nurse's empty spot by the hearth. Her sister has gathered them all in the now-empty storage room, barricaded the door from the inside, with instructions to remain there until the morning.

The servant girl circles the hearth one more time, topping off a final toast's worth of vessels. She goes back to her attacker's side as the widow begins to speak alone. Her words fill the room like wine in the goblets.

She speaks not of her husband's legacy, but of those who have stewarded it. The work of swineherd and shepherd, bringing young, struggling creatures into the world. The bent backs of farmhands harvesting flax and the calloused fingers that spun it. The arms that turned the spit and carved the meat, repaired fallen tiles from the roof and washed the house's walls each spring so that it stands gleaming white on the cliffs above the sea. She speaks of her own work and care, at the loom and among the accounts.

And then she speaks of her nights, alone amid the vast, empty expanse of her marriage bed, as the hearth's embers die, as her limbs soften with expended effort.

The fire at the hall's center quiets as well. Its rising smoke thickens until it is a grey white curtain. Odd shapes flicker against its screen. The serving girl recognizes forms and gestures—shadows playing out the lady's story. She risks a glance at the man next to her. His jaw is loose, his eyes hungry. She knows he reads a different tale in the words and shifting shadows, one in which the lady yearns with unmet expectations, a vessel waiting to be filled.

The lady's voice is whisper-soft, fading. The hearth light goes. Smoke thickens the air on all sides. Darkness hangs heavy, a long, breathless moment.

And then the hearth fire roars to life again, brighter and higher than any of them could ever stoke it. Flames like white gold fill the hall with light. It's empty, except for the lady and the serving girl, standing like cast pillars. They face each other across the hall's depth, faces mirrored with furious intent.

The serving girl blinks, and the room is as it was. The fire crackles. Guests shift in their seats. Her attacker glances around, uncertain.

She bends close again, drops a whispered instruction into his ear. "This is your time." He looks at her, wondering, but then, inspired, he pushes to his feet.

"Lady! Wait no longer! Don't let your—your fruits wither," he gulps as all eyes turn to him, but then lifts his jaw and abandons poetry. "Your body is too fine to lie down alone night after night. Don't wait until you're old and dry..."

"What—?" "—insults—would never—" Clamor rises across the room. They cry with shock, with outrage, with jealousy at one of their number who can speak his desires so baldly, but their voices are thick, slurred from wine and magic.

Many eyes turn to the oldest suitor, expecting him to frown away this outburst, to dismiss it as a raucous joke. It is what he's done before.

Instead, when light from the hearth flares up again, it reveals an answering fire in his eyes. He is drunk on more than wine. The magic of the lady's words has caught him as well.

He stands, and his voice is slurred. "Impudent pup." He puts out a hand, and the wall is there, a great ax displayed in pride of place. He tears it down. Reflected flame glitters along the blade.

The serving girl's suitor hesitates a moment. He almost recognizes the destruction he courts. No blows have been struck, yet.

But then a strung bow appears in the girl's hand. Is it formed from smoke and shadow? She reaches out with it. His eyes focus on her. He takes a staggering step, snatches it and shoves her away so hard that she stumbles and falls to the floor. He lifts the bow and nocks an arrow.

Time slows. The servant girl looks up, head ringing and heart full of fear.

The oldest suitor grins. He stands exposed. Wine and greed and hearthfire magic have taken his reason and care. They've wrapped him in certainty that he has only to make a threat and his claim will carry the day. Behind his bulk, the lady backs away.

Then a log in the hearth snaps. The suitor with the bow jerks at the sound—and releases his arrow. It flies across the hall, into the breast of the oldest suitor.

It takes a moment for the archer to realize what he has done, to gasp and stagger back. It takes only a few moments more for the supporters of the oldest suitor, his friends and cousins, to scream in outrage. Those still seated leap up. They press forward or lurch back. They pull more weapons from the wall, more bows and axes, swords and hunting spears. Their senses may be muddled by wine, but they understand what's needed now. Vengeance and counter vengeance burn through the hall.

The serving girl stays down, skuttles backwards to the nearest door, and then locks it behind her. She has a dire moment, afraid that the lady didn't make it out. But then they meet in the outer passageway and cry with relief to see only wine stains and dirt on each other's skirts. They hold each other tight, close their eyes as the screams and clashes of battle reach them through the intervening walls, as the firestorm of violence rages and finally dies away.

#

In the evenings, when the meal is done, I sit at my desk in my chamber. I write no more eulogies. Instead, I tally the health and strengths of our flocks and herds. I make plans for the future. I consult with the rest of the household about our stores of grain and cheese, the harvest of grapes we will send to market and those we will keep for our own use. The younger women of the house—serving girls they were called once, although now they serve themselves and each other, as much as anyone else—come to share a modest cup of wine under the light of my lamp. One of them says that an old beggar came to the door today. She gave him a good meal and let him rest a while by the hearth, before sending him on. I agree that she did well. The gods are satisfied by hospitality, but I have no patience for uninvited guests who linger. I have a house to keep.

© 2024 Chloe Smith

Chloe Smith

Chloe Smith works as a middle-school teacher, librarian, and copyeditor, and writes science fiction and fantasy stories despite all that. She was born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, and she lived in Texas and Washington states, New York City, and rural France before coming back to California. Her short fiction has appeared in Three-Lobed Burning Eye, Daily Science Fiction, Bourbon Penn, and elsewhere. Her debut novella, Virgin Land, came out from Luna Press Publishing in 2023.