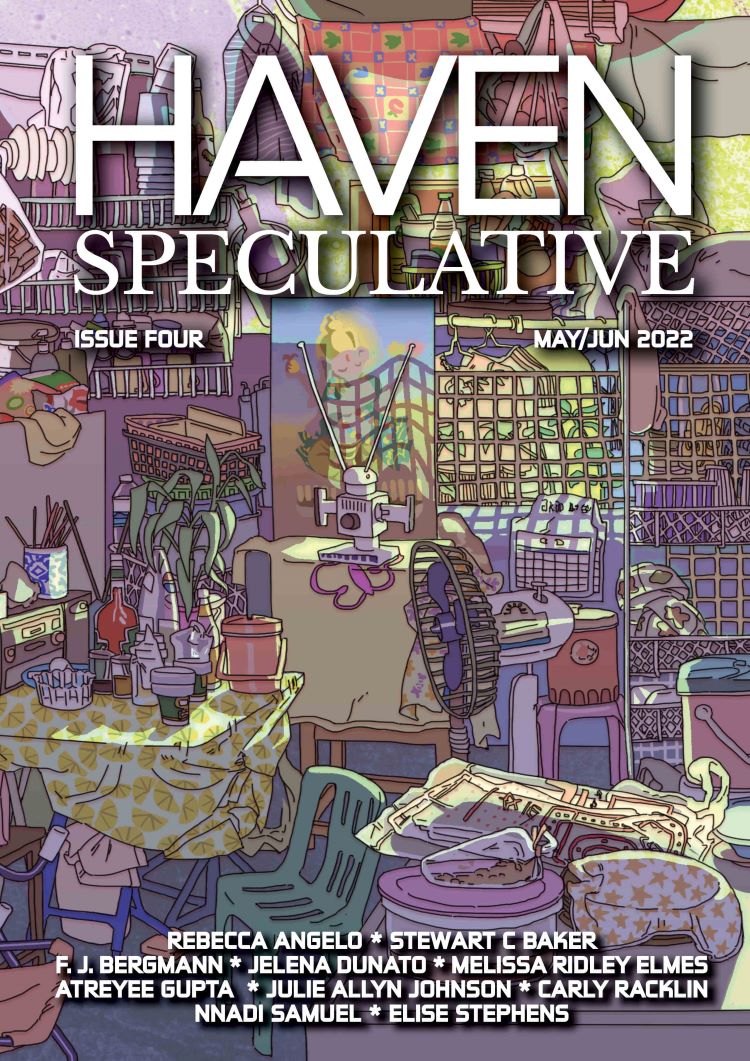

fiction

Focal Point

by Elise Stephens in Issue Four, May 2022

5752 words

Her world was gone, like a night sky stripped of moon and stars.

“They told me you fell,” Hilf whispered from the bedside. “That you tripped down the stairs from your studio and after that you didn’t look into their eyes.” His voice deepened. “Why didn’t you let them fetch a doctor?”

Her husband hadn’t removed his riding coat in his rush to see her, and she could smell the wet wool as she sat up and opened her eyes. As before, the darkness remained. Blind. Had she seen Hilf’s kind green eyes for the final time?

Estil groaned. Her eyes still burned with the afterimage of the painting that had blinded her: a winter garden glimpsed through a stone arch, twilight stars prickling crisply overhead as a golden sunset fingered the dry broken branches of nearby trees. In the garden’s center rose a birdbath, a cluster of bubbles frozen on its surface as though birds had just taken flight. The entire scene was splattered and stained with wet mud.

The painting had already destroyed her sight and, if anyone discovered how she’d hidden her secrets within the paint, she risked the loss of much more.

“A doctor can’t help,” Estil finally said, mumbling around her swollen tongue. She’d bitten it in the fall. “The blindness wasn’t from hitting my head; it’s from lumastrating.”

“But it’s not supposed to be dangerous, not to someone with your training, is it?”

“If the paints had been the diluted student-grade stuff that I used when I attended Aiken Lumidden, you’d be right,” she mumbled. “They wouldn’t have been dangerous.”

Hilf paused. “What kind of paints were you using, Estil?” His voice rang with fear and a trace of accusation. She felt like a scolded child.

“Lumidden paints.”

“And how did you acquire a set of illegal paints?” he asked slowly.

She turned her face away. These stolen, forbidden pigments had faithfully helped her shape the thoughts and emotions she could record nowhere else. She’d welcomed the icy power that gripped her bones with fiery aches, the acute, thoughtless agony that infused her muscles as she poured her torment onto the canvas. Her daily painting and its subsequent pain and exhaustion were her only weapons against the hollow pining for the baby who’d once slept in her arms. The baby Hilf knew nothing about, could know nothing about.

Hilf had accepted her reluctance to have children, made no qualms about her herbal contraceptive, but this was because he didn’t know that Estil’s illegitimate daughter had been born in secret two months before their arranged marriage and placed soon after with a foster family.

Estil had drowned her longing for her child in the paints, though she knew no good could come from them.

And now they had blinded her.

She’d fought with Hilf the night before, after he’d made an admiring comment about someone’s young sons, and then she’d risen early the next day, eager to paint her anger. She’d wanted to hurt him, and this intent to harm must have broken the dam of her repressed anguish and ripped away her sight.

Hilf’s whisper was full of fear and pain. “May I see the lumastration?”

Estil fumbled for his hand, then squeezed it sharply. “No! What happened to me could happen to someone else! I’ve turned the painting to the wall.”

She wished she could burn it, but she’d have to save the lumastration if she hoped for a chance at healing. Poison often carried its own antidote.

“Only someone who understands lumastrations can treat me,” she said. Maybe she wasn’t even curable. The darkness could spread to her other senses, stripping her of hearing, touch, taste… The thought made her want to thrash and scream. She bit down hard on her lip. She should have been prepared for this.

“I’ll send for the Lumanar of Aiken,” Hilf said, voice deepening with purpose.

“Not Aiken,” Estil said quickly. “No one from Aiken.” She swallowed her disgust. “I’d rather see Lumanar Hallis of Wessal.”

Hilf leaped to his feet. His boots thundered on the stairs as he shouted for a message hawk. As the odor of his wool cloak faded, Estil found herself recalling a different scent: rose soap from her daughter’s first bath, mingled with the tang of blood and joyous sweat of her new motherhood.

Lumanar Hallis was supposed to be compassionate. She hoped the rumors were true.

#

The madness of Estil’s malady stubbornly worsened with nightfall. As she lay unmoving in her bed, she thought she heard three times the soft cry of a baby and half-rose to scoop her up. Other times, she’d startle awake to the sharp smell of drying paint and a knuckle tenderly brushing her cheek, only to find no such lover beside her.

It wasn’t that she still longed for Amyr. The paints were twisting her mind back to when she’d wanted nothing more than to defy her parents. Fornali law considered a man and woman to be married after betrothal, and they’d betrothed Estil without her consent. Hilf Mogtin, her future husband, had been nothing more than three lines in a letter she received a week after she’d arrived at Aiken for her studies. She’d read the letter with cold fury, her life once again decided for her in her absence, and in her outrage, she’d laid eyes on Amyr, a handsome visiting instructor at the school. It was enough.

She’d been sixteen and unpracticed with the contraceptive teas. When a baby took root in her belly, she’d refused to shake it loose. Amyr left to attend a special commission after his term ended, and Estil faced her disgraceful expulsion alone. Only her mother had helped keep her secret, even from Estil’s father, taking her on an extended trip to a city on the Beyshiri border to “shop” for Estil’s wedding trousseau.

When the morning birds finally sang, Estil felt run through with fissures, like the cracked clay cup she used for storing her paintbrushes.

The message hawk returned early with Hallis’s reply, inviting them to present themselves at Wessal Lumidden. As the servants packed their things, Hilf and Estil ate a hurried breakfast. Estil had been humiliated by her slow stumbling to reach the dining hall, leaning on Hilf’s arm.

“Let me see the painting,” Hilf said quietly, setting down his spoon. “If I’m hurt by it as well, we’ll both seek the cure. It’s too strange, not knowing this thing that’s harmed you. My worries have built a monster out of it.”

“No—” she began.

He pressed on. “It can’t be as harmful as the war paintings they used on the front lines.”

“Hilf,” she said, making her voice tremble and hating herself for the artifice. “I don’t want to spread this. I’m ashamed enough by what I’ve done.”

This was true, but her real dread was that Hilf might see too much.

Estil had poured her heart into her paints, like they’d taught her to do in school. The passion, the pregnancy, the shame of expulsion, the lonely birth, nursing a sweet little girl at her breast and knowing she’d lose her forever in a few short days—they were all there, buried in shape, line, and color.

Hilf’s untrained eye might muddle the sentiments, and there was a good chance he’d confuse some details, but he’d get the gist. Estil wasn’t protecting Hilf’s eyes; she was protecting his heart. And, if she were being honest with herself, protecting her marriage. Or what little remained of it. Though she hadn’t yet met Hilf at the time of her affair with Amyr, Estil’s heart had sunk when she discovered the good man whose trust she’d betrayed.

Hilf sighed. “All right. The canvas should have dried by now. I’ll have it cut from its frame while it’s facing the wall. No one will see it.”

Estil hardly heard him. She’d had a childhood friend who’d delivered a bastard. The girl had raised the baby, but society had made her suffer cruelly. When she finally escaped, they found her in the forest with a belly full of poisonous sala berries.

If Hilf discovered the truth and turned her out, as was his right, Estil would have to return to her parents. Her father would insist that she be tattooed with a breakmark, the broken line lumastrated on her wrist proclaiming to the world:

This person broke faith. Her word means nothing now.

#

An updraft of mountain air shot past Estil’s face, whipping her hair. She tightened her grip on her horse’s mane, trying not to snatch at the reins in her fear. The howling wind seemed to rush from a large, open mouth as it tore up a sheer cliff face to her right. Hilf’s arm remained steady around her waist, reassuring her through wordless touch as he clucked softly to urge Thistle, his horse, forward.

They’d left behind the smells of livestock and dusty road hours ago, exchanging them for evergreens, moss, and mushrooms. Hilf’s personal attendant followed behind on a packhorse with supplies. Each hoofbeat on the rocky soil seemed to pound at Estil, reminding her that it was her rash impulses that, once again, were jeopardizing her marriage. Why couldn’t she have just written a confession of her foolish affair and her anguished separation from her daughter in a journal and then burned the damn thing?

Hilf was whistling a cheerful tune and Estil’s eyes stung suddenly as a realization hit her. She’d been wrong. She did want children with him. He’d be a patient, tender father. And he was so devoted. It made her feel sick sometimes, but also grateful.

They made camp later that night, and Estil sat carefully out of the way, trying to arrange firewood by touch while the servant pitched their tent and Hilf watered and fed the horses. Her husband still had the old habit of doing things himself. He hadn’t been born a lord. He’d once been a middle-class merchant, but successful business and court favor had elevated his rank.

The tingling smell of pine sap and rich earth seemed stronger here, but so did Hilf’s silence toward her. Ignoring the travel cakes and the meat that their servant heated for them over the glowing embers, Estil crawled into the tent and rolled in a blanket. When Hilf didn’t follow, she wondered if he’d somehow guessed the thing she was hiding.

She tossed and turned, her bruises and the hard ground preventing any comfort. It wasn’t until she started to doze that hissing words filled her ears. Her limbs stiffened.

He’ll find out, the hissing assured her. He’ll find out everything.

#

She awoke, hardly having slept, to the smell of bacon and a chorus of ravens conspiring to steal it. There was warming bread and brewing tea, the wind stirring dry leaves across the open ground, and the place felt empty. It took Estil a moment to understand why—Hilf had dismissed the servant. He was clearing his throat nervously. The bacon was burning.

“If something’s wrong,” Estil said, “you’ll have to lead me straight to it.” She sat on the cold ground and drew up her knees.

Hilf said stiffly, “I looked. At your painting.”

Estil shut her eyes. Even blind, her expressions could still betray her.

“I shouldn’t have looked,” he continued. “But avoiding it seemed so cowardly. I thought if I saw it, I might vanquish my fear.”

“What did you see?” she asked hoarsely.

“I’m no lumant,” Hilf said. “You told me that most people see a lumastration as a single, blended sentiment. Like a string of numbers all added together—the sum, not the individual amounts. It’s true, it all runs together for me, but even a dunce can recognize sadness, loneliness”—he hesitated, then added—“and grief.” The fire crackled as he chewed his lip. “When I lost Nirra, I felt...I didn’t think I’d live through it.”

Estil’s tears were hot against her eyelids. He’d lost his first wife in childbirth. Now his second wife had found a new way to break his heart.

“You can only lumastrate that which you know from personal experience, correct?” Hilf asked.

“Or memory,” Estil said faintly.

“That’s right. You told me that, too. And I see now that you’ve been miserable.”

Estil opened her mouth to contradict him, phantom winds roaring in her ears, but he said, “You loved and lost someone, I think. I can’t guess all the details, but I sensed them. Did you love another man before me? I’m sure you did. How does the world not fall smitten at your feet, Estil Lavrade? I don’t even know why your father chose me from your line of suitors. I wasn’t the richest or the most influential.”

Estil found her voice. “Mother chose you.”

A surprised pause. “Did she really?”

“She was always valued as a counselor with a sharp eye for the hidden vices and gracious motives that went overlooked by her peers. Of my suitors, she thought you were the least in love with yourself, and she liked how you tended your horse and hound personally. And you were courteous to your servants. She thought you had the strength to withstand a headstrong wife, and enough kindness to make her happy.”

“Yet despite your mother’s faith in me, I’ve failed at your happiness.”

Estil covered her face with her hands. Hilf didn’t suspect that her past love had tarnished his honor. He assumed it had taken place before their betrothal, assumed it had been innocent and chaste. He hadn’t recognized that Estil’s grief and longing was for her daughter, not her lover. She’d loved Amyr in a fleeting burst of passion. Mostly she’d loved the rebellion of loving him. He had been like a streak of wild blue paint, fading quickly as it dried.

Hilf scooted closer, the silence begging to be broken. It was her turn to speak.

“I’m sorry,” she said, knowing her words did little to ease his pain. “I should have—”

“No need to explain,” Hilf said. “I should have waited for you to tell me. It was I who did wrong.”

Hilf tried to slide his arm around her, but Estil shifted away, too miserable to let him touch her. He shouldn’t have to apologize for anything.

At last, Hilf passed her a plate of food, like a peace treaty, and Estil miserably ate the burnt bacon as ravens screamed above her.

#

The remaining ride to Wessal was silent and awkward, and by the time Hilf rang at the gate, Estil felt smothered by unuttered words. A lumant led them through the remains of a vegetable garden that smelled faintly of rotting pumpkin and mulch. The sounds of boisterous conversation and the noontime scent of savory stew drifted from a building somewhere nearby.

They were to stay in a one-room cottage on the school grounds. All the lumiddens were selective about their pupils but, unlike Aiken, Wessal accepted no generous “donations” in exchange for admittance; entrance was solely merit based. A lumant who’d completed an apprenticeship at Wessal could easily find prestigious work throughout Forna and its neighboring countries. Lumanar Shiruven Hallis’s seal of approval was all they needed.

Hilf set out their things, then stood in the doorway, letting the mountain wind flow inside. Estil sat at a small trestle table covered with a soft cloth beside a hearth that was burning cedar wood. Her body was stiff from the ride and her bruises throbbed. She wanted to read Hilf’s face, to see what signs of disappointment flickered there. His continued silence was like a gray film over a once-vibrant landscape.

Someone brought them bowls of stew and fresh bread, which Estil struggled to swallow. Soon after, there was a tapping at the door, a man exchanged a few words with her husband, then Hilf was at Estil’s side, speaking softly.

“The lumanar’s here,” he murmured. “You never told me he was blind.”

Estil faltered. “I didn’t think you’d—”

“How can a blind man heal you?”

“He’s only physically blind. He still lumastrates.”

“But how…” Hilf forced a deep sigh. “It doesn’t matter. He’s the head of Wessal, and I’m just a cloth merchant. What do I know?”

“He’s the greatest lumant in all of Forna,” Estil said firmly. She startled when Hilf kissed her forehead.

“I’ll take a walk around the grounds while you two get acquainted,” he said.

Her husband’s footfalls receded as the tap of a wooden staff and a softer set of steps entered the cottage. Estil straightened, her hands flat against the surface of the table.

“Lady Mogtin,” the lumanar began. “I’m Shiruven Hallis of Wessal Lumidden. I heard about your case from Lord Mogtin, and I must admit I’m most intrigued. I will do everything in my power to restore your sight.”

The lumanar spoke without bravado. His voice was old but well-tuned, like the low-note strings on the harp that Estil’s mother kept in her sitting room.

“You may call me Estil,” she said.

“And you may call me Hallis.” She heard warmth in his smile. “May I join you?”

Estil nodded. The other stool scraped the floor.

As Hallis settled himself, the scent of cinnamon bark, sage, and orange peels swirled through the room. The lumanar was famous for blending teas that countered or slowed the destruction that lumastration did to a painter’s bones.

“I’ll be frank,” Hallis said, thumping a heavy vessel onto the table between them. “I can do next to nothing before I see the lumastration that caused your illness.”

“But you’re blind.”

“You sound like your husband.” Hallis’ tone was gentle.

“I’m sorry. I just…” Estil bit her tongue. “I’m sure you wouldn’t have let me come to you if you didn’t think you could help me.”

His reply held no bitterness. “My eyes may have clouded to the world, but not to lumastration. I see the paints more clearly than ever.”

Estil nodded to herself. She’d once heard a minstrel sing haunting arias, only to discover the woman had been born deaf. The limitation hadn’t stopped her gift.

And yet, her heart twisted. If Hallis looked at her lumastration, his trained perception would extract each nuance, peeling the layers back and sorting everything into the proper pile of her life’s story. He’d read the details of her love affair and her punishment. He’d see her motherhood and her heartbreak. He would stare at her naked soul.

Would he tell Hilf everything he’d seen? Estil could bear the shame of the lumanar seeing her secret, but not the thought of him bringing the wretched news to Hilf. She couldn’t let him humiliate her husband; she’d rather tell Hilf herself.

“I think I need something to drink,” she whispered.

“Try this.” Hallis pushed the vessel he’d brought toward her, and Estil lifted its crockery lid, the smells of mint and ginger rising from it in waves. She took two deep swallows and the chill in her limbs receded.

“How can you heal me if you’ve never been able to heal yourself?” she asked.

Hallis chuckled patiently. A question he must have received countless times. “Some of us require great courage to face the darkness that has made us ill and thus to conquer it. And some of us use our courage to conquer things that threaten that which we hold dear or sacred. But we must all sacrifice for our victory. I willingly paid this price in the war, and I’m grateful it’s behind us now.”

Estil swallowed carefully and said, “My vision may be restored once you’re through with me, but I believe the life that awaits me is already ruined by my poor choices. My marriage has no chance of surviving this.”

“Tell me,” “Hallis said, “is your husband the punishing type?”

She shook her head slowly. “That’s not in his nature.” Her palms went cold as she thought of her own father’s anger. “But when someone’s honor is tarnished, many good men become little more than beasts.”

“Then I’ll say this,” Hallis said. “You came to me for restoration, and I intend to give it, and not just to your eyes.”

“Will you tell Hilf what you see?”

“Not without your permission.”

If Hallis would guard her secret, then she could focus on the cure. Whether or not she’d tell Hilf was a question for later.

Estil breathed slowly, the air shaking in her throat. A sharp ache was spreading through her chest, and she was sure that only tears would ease it.

As to the dread in her belly, she might have to learn to live with that.

“Let’s begin,” she said.

#

Estil sat on a weather-worn bench outside the cottage, her cloak wrapped tightly around her shoulders, lungs dragging in the mountain air. She was shivering but couldn’t tell whether from anxiety or cold. Any minute now, Hallis would pronounce judgment and she’d hear the disappointment in his voice, smell his condemnation like a rancid spice on his clothes.

When at last he called her, she fumbled the cottage door open, but tripped over the threshold and had to lean hard against the doorframe to regain balance. “Please,” she said, almost too quiet to hear her own words, “just tell me what you saw.”

“I’ll list the patterns I observed,” he said, his voice strong and firm, like a teacher delivering a lecture. “First, a love that was lost.”

Estil saw again the three perfect stars from her painting. It was the view from Amyr’s window on the first night she’d spent in his room. They’d echoed the cluster of dark freckles on his chest.

“A beloved child who is no longer in your care,” Hallis went on.

Bright iridescent spheres of soap bubbles, hidden in a birdbath—for when she’d washed and kissed her daughter’s silk-soft skin.

“A sense of imprisonment, set by strict parental boundaries,” Hallis finished, his voice gentle.

The stone wall, patterned after her childhood bedchamber, where she’d been confined as punishment for so many hours of her life.

Estil clawed at the doorframe to keep herself from dropping to her knees. In her mind’s eye, she saw again the vermilion and amber with which she’d painted the stone archway, mirroring the rage she’d felt when her mother had said, This child is a dreadful mistake. She’d wanted an ally, someone to support her far-fetched dream of raising the child in secret, but she’d had to settle for an accomplice to help her bury the traces of her misdeed.

Estil lurched back to the table beside Hallis, smacking her knees against its leg and biting back a groan as she took three more sharp gulps of tea.

“I agreed to heal you because your case is quite rare,” Hallis said.

She forced a laugh. It sounded more like a choked sob. “Birthing a bastard is hardly a rarity.”

“Not that.” His voice was kind. “A lumastrated wound that fully blocks a sense takes great skill and focus. Few lumants can paint with such precision. How long did you study at Aiken?” Hallis asked.

“Two and a half months.”

“Remarkable. You believe, I’m sure, that it was your untrained use of lumidden paints that hurt you. But I’m convinced you’re sick because of what you painted, not because of what you painted with.”

For a moment, Estil imagined herself again in the tower of Hilf’s manor, painting with wild strokes, her heart full of more sorrow and regret than she could carry. She shuddered, but some strength from Hallis’ presence helped her to hold her tongue.

“Tomorrow,” Hallis said at last, “I’ll paint an inversion for each layer of this lumastration, and we shall begin its unraveling.”

“But if I can’t see, how will a painting help?”

“Lumidden paints enhance and animate that which already exists. You’re consumed by secrets, and their hunger for obscurity became the focal point that manifested as a loss of eyesight. Yours, I believe, is reversible.

“You can still see,” Hallis said, rising from his chair. “You just don’t know it yet.”

#

The next morning, Hilf kissed Estil and took Thistle riding while Estil sat, feeling silly, and obediently tried to observe the painting Hallis made for her. An assisting lumant stood ready at the door, occasionally fetching or adjusting tools to assist the lumanar.

By the midday meal, a dim light had begun to penetrate her vision, giving blurry shape to the windows, lamp, and hearth fire. By evening, traces of color were leaking through, the shapes assuming enough substance that Estil could stand and move about the room without smacking into walls or bruising her shins. As unbelievable as it had seemed, Hallis’s painting was taking effect. By early evening, she blinked and the final film lifted, leaving her with clear, restored vision.

Estil gasped, absorbing the vibrant gold of the firelight, the dance of shadows cast by the table and bench, the gray and beige veins of the floorboards. Her eyes stung and her throat closed as she studied the luminous colors of the Hallis’s painting: a springtime garden, an inversion of the muted, decaying tones of her winter scene.

“What do you see?” the lumanar asked.

“I see life. A second chance where before I saw only broken dreams and sadness. I don’t know how you’ve made me feel hope, but I feel it. And yet, something remains unfinished.”

“What is it that isn’t finished?” Hallis asked, his face lost behind a massive gray beard, his eyes deep and kind. He was nodding, as if he knew her thoughts.

“Could you spare me a small canvas, paint, and a few brushes?” she asked. “I need to make a lumastration of my own.”

#

She dressed for her meeting in a simple tunic and leggings, then braided her hair into a long cord. Hilf needed to see her as a woman, not a lady; as a wife, not a descendent of a noble bloodline who outranked her husband; as a human, not a portrait. Estil had spent her first day of renewed sight inside the cottage, painting furiously.

It was now evening, and she had two lumastrations to show to Hilf: the winter garden scene that had blinded her, and a new piece that might yet ruin everything. The winter garden scene was already shrouded and waiting for Hilf in the courtyard. Estil would bring the new, still wet painting herself.

A few months after Estil had married Hilf, her husband had caught his household steward falsifying the books and stealing money. The man had been Hilf’s friend and trusted adviser. After checking the numbers twice over, Hilf had confronted the man, listened to his confession, then dismissed him with no time for further explanation. “In realms of honesty, there are no second chances,” he’d explained to Estil after letting the man go. “Lies only grow easier to tell.”

This logic had seemed admirable to her at the time, but when Estil considered Hilf’s strict integrity now, her breath rattled in her chest.

He was waiting on a stone bench beneath an apple tree and leaped to his feet as she approached, arms laden with canvas.

“How are you?” he asked softly. “Hallis said that when your sight returned, the first thing you wanted to do was paint.” There was hurt in Hilf’s voice.

“I’m much better,” Estil said, “but I feel my health won’t last unless I do this too.”

“You mean continue lumastrating? Of course, you must. We’ll hire a tutor. Or you could take a course when—”

“Not that. I mean I need to explain what I’ve painted. To tell you everything.”

He sat, sensing her sobriety.

Estil carefully leaned the smaller painting at an angle where Hilf couldn’t see it. Then she drew the sheet off the winter garden.

“You saw this once before, but you didn’t fully understand it, and I didn’t have the courage to correct you. You noticed my sadness”—she traced the shape of the broken flower stalks—“my loneliness”—she indicated the fading sunset—“and my despair”—she spread her fingers over the darkened sky. “What you didn’t know was that the lost love was my daughter. I delivered her in secret and had to give her up.”

“A daughter?” Hilf whispered, his voice rasping. “Of course, she’s not mine.”

Estil drew a long breath. “During my Aiken studies, I met a lumant there and—”

She looked into Hilf’s face and the words died in her mouth. The anger in those green eyes was quickly drowning in tears. He looked away.

“Then we discovered I was pregnant.”

Hilf tried to speak, failed, then tried again. “Were we betrothed when you…?”

She didn’t let herself hesitate. “Yes. I knew what I did, though I didn’t know who I was doing it to. You were just the faceless figure of a husband my parents had chosen for me, and I wanted to fight against them.”

“Did you love him?”

She’d never heard Hilf sound so frightened. The real question, she knew, was, Do you still love him?

“I think I loved the idea of him. But that’s buried now. I choose you, Hilf, and I love you, though goodness knows I’m not the country’s best wife.” She forced herself to keep talking. “All I’ve done since we married is look back at my mistakes. My time spent lumastrating was my escape. It was where I buried the things I couldn’t tell you. I broke faith, and—”

She faltered as Hilf’s mouth tightened and his eyes glittered like ice. He wouldn’t hit her, she knew, but he had the right to send her away. He’d done it before.

She tried to keep her face still as he wrestled with himself, rage crashing against an affection that flamed in his green eyes—the eyes she had feared she’d never see again.

And then he was standing before her, his shoulders slumped but …. The rage hadn’t won.

Estil felt like she was melting between the cobblestones. “My father knows nothing,” she whispered hoarsely. “The deception was mine alone. I only ask that you see me for who I am.”

She drew a steadying breath and turned the smaller lumastration toward him.

Estil had employed an impressionistic style for this painting, pouring her emotions into its brushstrokes. In the center stood a stag with antlers, limbs, and throat snared by vines and brambles, a scarlet fire lapping ravenously at its flank. Its head, though hopelessly tangled in the branches above, was twisting toward a shimmering curtain of rainfall sweeping across a meadow. The fire’s outer edge resembled her father’s terrifying seat of justice, and the droplets of blood clustered on the stag’s forelegs were smudged to resemble a tiny, red handprint. The rainfall in the distance had a green-blue sheen that exactly matched Hilf’s eyes when he smiled.

Estil met her husband’s gaze. “As I am. Caught between. Nearly consumed by fire and praying for the rain.” Hilf seemed to be studying the stag’s antlers.

“Its antlers are its pride,” Estil murmured, “and it was my own proud defiance that birthed this deception and heartbreak.”

The stag wasn’t waiting for rescue; it was hoping the rains would come and loosen the vines. But that didn’t stop it from thrashing and risking strangulation. Estil shuddered as she realized that this was her own admittance that she’d rather take her own life than live under her father’s disapproval.

She spoke carefully. “I have my own scars and mistakes. But my story isn’t over yet.”

She looked into the coursing, lumastrated flames and shuddered. The stag stood firm with the certainty that a choice would be made, that no fate would be decided for him. His ears, nose, and white-tipped tail pointed toward the falling rain, beseeching it.

“I know you, and how good you’ve been to me.” Estil whispered this so softly that Hilf had to lean forward to hear. She’d laid her fear, self-hatred, and shame inside the fire, and in the rain she’d placed the trembling hope that Hilf would offer her another chance.

“I failed you,” she said into his silence, “but I’m not running away. Not unless you want me to leave. I await your choice.”

Hilf was on his feet in a sudden, swift movement and she held her breath, bracing herself for whatever outburst he’d prepared, but he only sank to his knees and opened his arms with the slow care of a man who wished not to startle with his movements. Estil stared, blinking hard at his wordless invitation. She took one hesitant step forward, stopped, and she was running the rest of the way with the clumsiness of a blubbering child, crashing onto her knees and pressing her face against his chest.

“That took great courage to tell me,” he murmured against the top of her head.

She had no response, her stomach knotting as she recalled how he had fed her soup with his own hand, kept a firm grip on her elbow when he helped her dismount from their horse, discussed their estate business as one equal to another, and now, in the moment she’d confessed her betrayal, he’d complimented her on her courage.

“My brave Estil… I want you at my side—a woman who faces her mistakes and speaks the truth at her own peril. It’s all the more reason I’d be a fool to cast you away now.” He touched her chin. “But this daughter of yours”—her heart plummeted and she pulled back to look at his face, but he was smiling— “…Should be raised by her mother.”

Something burst in Estil’s heart, sound and color crashing over her like waves that wouldn’t let her up for air.

“But the shame,” she murmured. “I can’t do that to you.”

“A couple can’t take in an orphan in as their ward?” He raised a mischievous eyebrow and Estil collapsed against him. Hilf’s chest shook in a burst of surprised laughter. This was the closest she’d ever felt to him—no cavity to shelter secrets and no furtive grief to press them apart as they wrapped themselves in one another, kneeling in cold mud, the sky above shining a rich, clear blue, the mountains sparkling with snowy brilliance. On the ground between them, a bright, purple bloom pushed up through cobblestones and withered leaves.

It was the exact color of unexpected joy.

© 2022 Elise Stephens

Elise Stephens

Elise Stephens credits much of her storytelling influence to a lifelong love of theater and childhood globetrotting. Much of her work focuses on themes of family, memory, and finding hope after a devastating loss. She is a first-place winner of Writers of the Future (2019), and her fiction has appeared in Analog, Galaxy’s Edge, Escape Pod, Writers of the Future Vol 35, and FIYAH, among others. Elise lives with her family in Seattle in a house with huge windows to supply the vast quantities of light she requires to stay happy. Elise is currently seeking representation on her next science fiction novel. Find her at www.EliseStephens.com.