FICTION

Ghost Apples

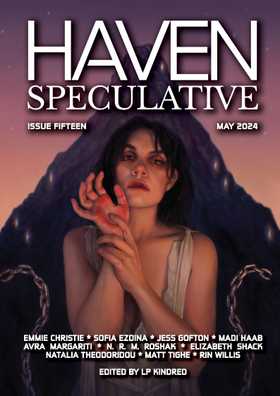

by Madi Haab in Issue Fifteen, May 2024

Another dead rabbit had grown out of the snow.

Cathilde pulled her foot back, shuddering at the sight. The rabbit was just outside the tent, laid out like an offering. Beady brown eyes stared up at a sky the colour and texture of meringue; its soft white fur rippled in the crisp wind, and a spray of red berries grew out of its mouth, covered in a thin lace of frost.

The first time it happened, Aglahé had sliced open the rabbit's—seemingly innocuous—belly to reveal a furl of pale flowers growing between its organs. The second time, a tangle of roots had grown overnight next to their tent, a white pheasant encased in its coils. The third, they had opened a handful of chestnut shells, only to find quail chicks nestled inside.

Cathilde had yet to grow inured to these gruesome discoveries. She looked around in hopes of spotting Aglahé's dark head against the snow, but she was alone. No one—nothing—around except the tall spare trees standing sentinel, boughs heavy with last night's snow. Besides, she knew what Aglahé would say. It had been two days since they last ate something other than their diminishing store of salt meat, and they could not afford to pass up a proper meal.

Cathilde took a deep breath and plucked the rabbit from the frozen earth. Even through her mittens, she hated the sensation, the dead weight, the unnatural slump of the small body. She held it at arm's length as she waded through the snow, then dropped it to the flat stone Aglahé used to skin and butcher game.

She ducked inside the tent, where her lute was waiting. The bent neck gleamed temptingly in a strip of daylight, but she helped herself to one of Aglahé's axes instead. How many blades Aglahé needed was a mystery for the ages, but this one looked as sharp as any, a menacing strand of silver running along the edge. Cathilde clutched it to her chest and returned outside, trying not to think of altars and sacrifices.

You can do this, she willed herself. She gripped the handle with both hands and lifted the axe overhead, her heart high in her throat. Just one clean, confident cut, like Aglahé would do.

She shut her eyes, hard.

"Cat?"

Cathilde yelped. The axe dropped to the stone with a sharp noise, and a bird took flight in the mocking echo of her voice.

"It's me," Aglahé said, the words fluttering with mirth. Her green eyes were shining, her freckled cheeks bitten red with cold. She slunk between the trees without sound, nimbler on her snowshoes than should be possible, then balanced her bow and quiver against the peeling trunk of a birch. She smelled of earth and leather, and her hair was spattered with snowflakes like stars in the night sky. Then she saw the dead rabbit on the stone. "Another gift?"

Gifts. That was what she called them. Ever the optimist, Aglahé saw offerings where Cathilde saw threats and ill omens.

It took Cathilde a few tries to find her voice. "Yes. It was right here," she said, gesturing towards the deerskin flap of their tent.

Aglahé smiled, the only warm thing these days. "Can you boil some water? I'll take care of it."

Cathilde hesitated. She wanted to learn, wanted to be useful at something other than just melting snow and warming the bearskin they shared. She was the reason for their exile to the mountains' neverending winter, after all. But then Aglahé unsheathed her knife, and Cathilde turned away, face burning.

The one time she had watched Aglahé dress a catch she nearly fainted. She even complained when they stole a squirrel's hoard from a tree hollow. Stupid, she knew now. Spoiled. Back home, Cathilde had never been privy to what happened between livestock and dish, between calf and veal or cow and beef. Sometimes, if she looked out the window of her carriage on the way to the summer palace, she would see white cottony sheep dotting the fields, or perhaps glimpse her brother's catch when he and his hounds returned from the hunt. All she knew otherwise was the final dish, plated on silver or porcelain: duck roast glazed with honey, steaming venison pie, lamb fragrant with rosemary.

A shard of grief lodged in her throat: for her lost home, for her dead family, and for herself, the lone exile. She had been worth something, on the other side of the sea. But what good were dancing and poetry in a land as merciless as this?

Cathilde maneuvered Aglahé's bow into the tent, then sighed. Of course she had let the fire go out. She knelt next to the fire pit, steel and flint in hand. It took her a few tries to light a spark, but the fatwood shavings caught flame, and she fed the newborn fire a few twigs. Outside, Aglahé's axe struck, the sound clean and sharp. When the smoke rose in pale volutes towards the top hole of the tent, Cathilde filled their cauldron with snow and watched it melt over the fire.

They had a feast, by Cathilde's new standards: rabbit stew with mushrooms and some kind of herb Aglahé could only name in her mother's tongue. Before long, it was warm enough inside the tent to peel off their layers of fur and wool. They shared the remaining nuts from the squirrel's hoard in lieu of dessert, and even without wine Cathilde felt that lazy, contented glow pool inside her as she aimed acorns at Aglahé's open mouth.

By the time they ran out of acorns, Cathilde had almost forgotten the rabbit's mysterious appearance. "Sing something for me?" Aglahé asked, firelight flickering on her cheekbone.

This, at least, Cathilde could do. She set the lute into her lap, tuned the courses, and soon her fingers were dancing to the cracks and pops of the fire. Her voice leapt into the melody, easy as breathing. It was a song of courtly romance, a song that made no sense this far from the country of her birth, but Aglahé did not seem to mind, and a smile stretched across her flushed, freckled face as she listened.

#

Aglahé left early the next day to check on her traps, and Cathilde was determined to make herself useful in her absence. She pulled on all her layers of wool and deerskin, tied her belt, and wrapped herself in her fur cloak before wading out, a basket hooked on her arm. The crisscrossing rawhide of her snowshoes left recognizable tracks in the snow, but she took care to mark her path with little notches in the bark of the trees she passed by.

No getting lost or calling for help this time. She would make her way back home on her own.

Home. The word felt strange, alien, like an intruder barging into her mind. Home used to be airy, arched ceilings of marble and gold, green gardens with rose hedges and topiaries. Then the castle fell, and for a short time home was an orphanage half a world away, roundwood and a woodstove and a flat roughspun pillow she wet with tears every night.

It was where Cathilde would have been married, had she not run away with Aglahé instead. Now home was the bearskin they shared at night.

Warmth bloomed on her skin at the thought, somewhere beneath all her layers of hide and leather. Focus, Cathilde admonished herself, and forced her attention back to her harvest. It was hard work, finding the sprays of dock plants bent under the snow and pulling roots from the frozen earth. But her basket filled, one pinecone, one mushroom, one thistle root at a time. She had no idea if they were edible, but she could bring them home—that word again—and Aglahé would know.

Despite the effort, the cold found its way into her clothes. Her panting breaths rose in white puffs before vanishing into the winter air. The sun was hidden behind a colourless sheet of clouds and hardly produced any heat. Cathilde tightened her cloak around herself, then started tracing back her steps.

A flash of colour between the pale boughs caught her eye. Twin apple trees, sinewy limbs heavy with fruit, dangling like garnets on long, drooping stems.

Cathilde could hardly believe her good fortune. She plucked a first apple off its branch. No need to even twist the stem: it gave way at the merest tug, sending down a light dusting of snow, like powder sugar on confections. The other apples shivered on the branch, thin ice shells shimmering in a slant of daylight. Unable to resist, she bit into the ripe fruit. It crunched satisfyingly under the tooth and spilled its tart icy juices down her chin, and only the core remained in just a few bites. The other apples she dropped into her basket, nestling among the mushrooms and sheaves of roots and stalks.

One last apple, high up the tree. She clung to a thick branch with one hand, stuck her snowshoe into the fork at the base of the two trees, and that was when she saw it. A bony face at her feet, a bleached skull too enormous for a deer or even a moose. Something was staring up at her from the hollow eye sockets.

Too late, she realized the trees were not trees, but antlers.

The ground rippled at her feet, and the small, snowy hillock rose before her. Cathilde screamed. In her haste, she stumbled and dropped the basket, mushrooms and apples scattering about the crust of snow. She did not care. She kicked her snowshoe free and ran as fast as her legs allowed, not sparing a single glance over her shoulder. Bare branches whipped at her face; old, gnarled roots clawed at her feet, and her blood beat so hard against her eardrums she heard nothing else.

The snow crumbled under her weight. Cathilde was in free fall, carried away by the toppling snowdrift that hid the edge of a cliff. The world was a whirl of whites and grays; her snowshoe caught on something, and her ankle burst with pain. The snow at the bottom of the cliff swallowed her, and then all was quiet, save for her heart drumming in her ears.

Her ankle throbbed, and there was snow on her face, in her collar and her boots. The cold seeped through, layer by layer, till it burrowed into the very marrow of her bones. Her teeth chattered, then stopped. She had to get up. She had to find her way back, but she pictured herself dusting the snow off her face to find that dreadful apparition bent over her, and she could not bring herself to stir an inch.

Cathilde started to cry, somewhere under the snow. "Aglahé," she whispered, tasting the cold on her lips, not daring to call out in case something else answered. Perhaps it was better she stay here, anyway, where she could not be a burden anymore. Not like she even knew where to go, now that she had lost her way, and not like she could go anywhere in the first place, with pain flaring red and hot from her ankle.

At last the cold soothed her throbbing ankle, and then even the cold itself was not so bad.

#

Cathilde dreamed. She dreamed of her fine bed of duvet and silk, the sprightly scent of cut grass leaping through the open windows, lace curtains billowing in the breeze. Someone's lips on her brow. Her brother, she knew, his collar smelling of leather and the warm, primal scent of his hounds.

Tears scalded their way down her temples. They burned holes through the dream, till all that remained were the cracks and pops of the fire, the scent of pine needle tea, the cozy weight of the bearskin on top of her body.

Aglahé's thin wrist in her hand.

Cathilde held her breath, not daring to move. Aglahé's breasts were pressed up against her shoulder blades; she was asleep, one arm thrown over her and one knee tucked between her legs. They were lying skin to skin, the seam of their bodies burning with shared heat.

Lying like lovers. A tender ache bloomed low inside Cathilde.

Slowly, slowly, she rolled over to face Aglahé, wincing when her ankle whined in protest. Aglahé's lashes cast delicate shadows on her freckled cheekbones, and a thick, liquid strand of hair swept across her face. Never had Cathilde wanted to lie like this with any of her past suitors or the fiancé the orphanage headmistress had elected for her. But now, she burned to press her lips to Aglahé's.

Instead she settled for brushing that lock of hair from her face, but even the careful touch of her fingers was enough to rouse Aglahé. She was awake all at once, wide green eyes warmed to hazel in the firelight. "You're awake," she said, the relief stripped bare in her voice. Then she slipped out from under the bearskin, unbothered by her own nudity. She unhooked the kettle from the fire and poured a steaming mug of tea. "Here. Drink this."

Cathilde sat up with difficulty, careful to keep the bearskin tucked under her armpits. She accepted the tea and inhaled its fragrant steam. "How did you find me?" she asked, letting the mug warm her hands.

The look on Aglahé's face was opaque, almost distant. "I found you outside the tent."

Just like another dead rabbit. A shudder ran through Cathilde despite the scalding tea. Then she saw the red fruit piled in a corner of the tent, the skewered apple wedges turning golden over the fire, and blanched at the sight. In her mind's eye, she saw again the shimmering red apples, the skull antlered with trees, the frozen earth rumbling as the creature stood.

Aglahé's gaze followed Cathilde's, then caromed away as heat coloured her face. "You knew," Cathilde blurted out, and the contrite droop of Aglahé's head was all the answer she needed. "You knew about that—that thing."

Her green eyes flicked once to Cathilde's face. "I suspected. I've heard of things like it. Ancient things that just ... keep changing instead of dying."

"Why didn't you say something?"

Aglahé blew out a breath, as though in defeat. "I didn't want to scare you. I just didn't count on you running into it in the woods."

Hearing it hurt more than she expected. Of course. Poor little Cathilde, always so scared, always so useless. She took a sip of tea, welcomed the scalding pain on her tongue and down her throat, then set the mug aside to clutch the bearskin to herself. She refused to cry, though, so she took a steadying breath and blinked the prickle out of her eyes. "What does it want?" she asked, when she trusted her voice again.

Aglahé moved to the fire and turned the skewers over. "Who can know for certain? But whatever its reasons, I don't think it means us harm. Hence ... the gifts."

Cathilde's blood ran cold at the thought. "We shouldn't eat those."

"Cat, we need to eat. Especially you." Aglahé lifted one of the apple skewers from the flames, then risked a careful bite, evidently to prove a point. "What were you even thinking, leaving like that on your own?"

The smell of cooked apples wafted towards her, but Cathilde ignored her grumbling stomach and hugged her folded knees to her chest. "I wanted to be useful," she whispered.

The skewer hung between them. "Useful?"

"I'm worthless," she replied, her breath hitching in her throat. So much for not crying. "You're the one keeping us alive, and I can't do anything except sit around because I mess up everything otherwise, and I'm ... I'm scared."

Aglahé stared at her, two red splotches bright on her cheeks. "Scared of what? The creature?"

"Scared you're going to tire of me and leave me behind."

Her arm dropped back to her side, the skewer forgotten. "Oh, Cat." She drew closer and cupped Cathilde's face with her free hand. "You're far from worthless. You have a gentle heart and the most beautiful voice I've ever heard. That's worth something."

Cathilde turned away from the touch. "Where I come from, maybe. Not here."

"Yes, it does," Aglahé said, like a lute string snapping. "You think the village wanted anything to do with the half-breed daughter of a trapper? All my father ever taught me was survival. The songs, the music, the soft, pretty things, none of that was for me. And then you arrived here and it was like you were made of those things."

Cathilde stared, voiceless. Two teardrops fell from Aglahé's lashes, but she did not wipe her face. "Do you remember when you played your lute for me the first time? That was worth something. That was worth more than you know."

How could she forget? Her lute was the only thing she had brought from home, and what brought them together. This time, it was Cathilde who reached for Aglahé's face. The tears burned even hotter than the tea as she brushed them off her cheeks; then she plucked an apple wedge from the branch, bit off one half, and brought the other to Aglahé's parted lips.

The apples were sticky sweet, and their heat unfurled in gentle tendrils to pool inside her ribcage. They tasted just as sweet on Aglahé's mouth, her tongue, her fingers, the lingering salt of her tears like fleur de sel sprinkled on caramel. One appetite sated, Cathilde pulled Aglahé back under the bearskin, certain she could see the pulse thundering against her breastbone.

Their bodies met, bronze on porcelain, and eager, fumbling hands explored every uncharted inch of skin. Warmth turned to heat and filled every space inside her, banishing even the memory of the cold. The last of the chill melted away, till the inside of the tent was thick with their mingled breaths and this new, fragile thing sprouting between them, long before the spring thaw.

#

For once, Aglahé did not rise with the sun. She only roused to coax the barest embers back to life in the fire pit, then slipped back under the bearskin. A thin plume of smoke shivered in the gray morning, and birdsong poured over them from the top hole of the tent. Aglahé's hair smelled of winter and woodsmoke.

She still tasted like apples.

"When your ankle is healed, I will teach you what I know," Aglahé announced after, still breathless.

Cathilde broke into a smile so expansive her cheeks ached. "And I can teach you the lute in return."

"Sure, if you want to laugh at my expense."

Her own laughter joined Aglahé's. Then Cathilde sat up to reach for the lute, paying no mind to the bearskin falling off her body. The shell of polished rosewood was cold against her breast, and droplets of light skittered down the strings as she tuned the courses. Then she plucked the chanterelle, drawing a clean, crisp note out of it, and let her fingers run where they willed. The song of the lute twined with the birds chirping outside, and soon she joined her voice to this extemporaneous recital, humming half-forgotten fragments from the world she left behind.

Aglahé watched her, a soft smile on her lips. She waited till Cathilde's fingers grew lazy on the courses to start pulling her clothes on—"the traps," she sighed in answer to Cathilde's questioning eyebrow. She belted the leather cord around her waist, pulled her mittens on, then lifted the deerskin flap of their tent with an arm.

Morning light poured inside; Cathilde squinted against the sudden brightness, and it took her a moment to look up from the carved lattice of her lute's rosette and see what Aglahé saw.

Twin apple trees, shimmering with fruit of hollow ice.

A dead rabbit hung from the creature's jaws, held by the flowering tendrils growing out of its ears and pink little nose. The creature laid it almost reverentially in front of the tent, only a few paces away. Then it lowered itself to the ground, almost disappearing into the snow. Were it not for the empty eye sockets on that bleached bone head, one might see nothing but a pair of apple trees and a snowy hillock, dotted with mushrooms and furred with moss and dry dock stalks.

The fear was gone. Cathilde plucked the chanterelle again, tentatively this time, and soon the airy, playful notes of a new tune were swirling in the pure winter air. Aglahé sat back on her heels, one hand clamped over her mouth. The creature sagged into the earth, as though in relief.

Cathilde closed her eyes as she played, her fingers light on the courses. The forest listened.

© 2024 Madi Haab

Madi Haab

Madi Haab is a queer, neurodivergent, and half-Moroccan writer from Montreal who explores identity and relationships through speculative fiction. In 2023, her story “Blabbermouth” received an honourable mention from the Penguin Random House Student Award for Fiction, and her short fiction has since appeared in Hexagon Magazine and is forthcoming in Augur Magazine. When not writing, she dabbles in singing and art, and likes naps and videogames a little too much. Find her at lamotdite.com or on Instagram, Bluesky, and Twitter @lamotdite.