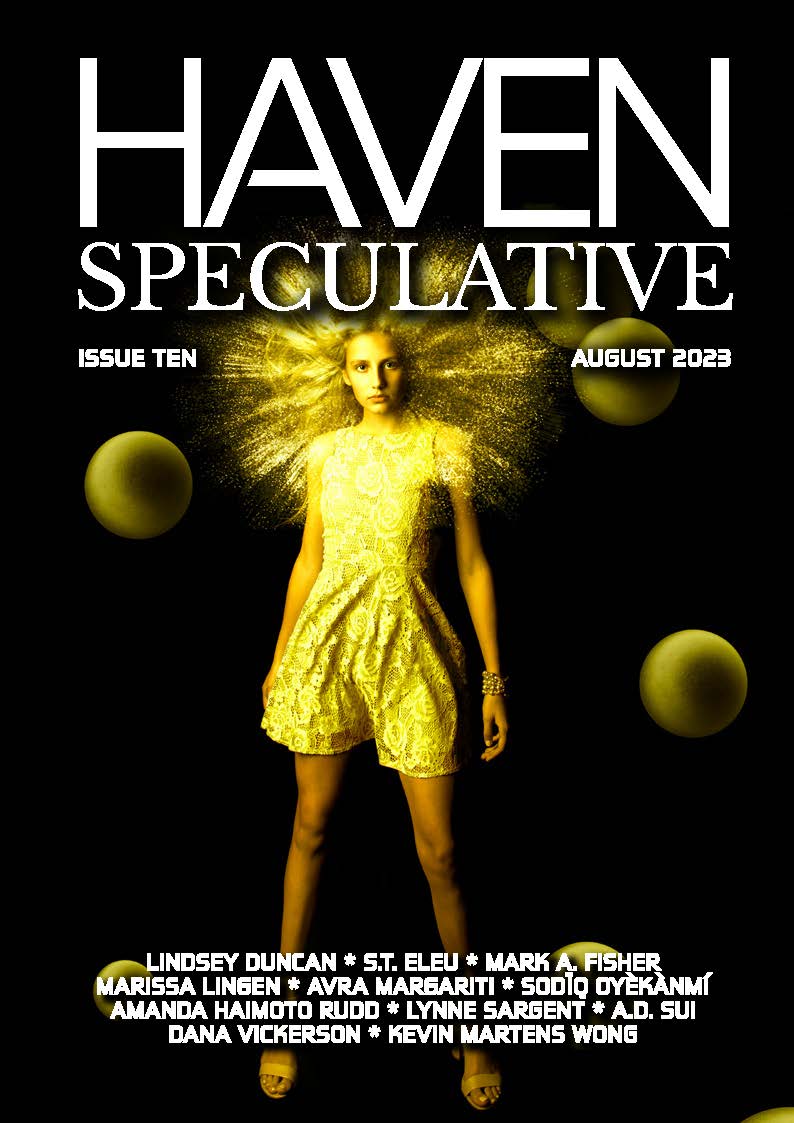

fiction

The House of Mourning

by Dana Vickerson in Issue Ten, August 2023

1195 words

Lena’s still in the baby doll dress and Doc Martens she wore to Andrew’s house on the night she died. The floors in the House of Mourning are wet and sticky, like the rotting residue in some long-forgotten building, sucking at her boots as she walks the endless halls. There is only one door, but there are many mirrors. Some she can see into, some she can’t, though this is no fault of the mirrors. Most are cloaked in a darkness so deep Lena feels as though she could lean into it and be swallowed whole.

The mirrors hold the lives of everyone Lena has ever known. H er second-grade teacher. The bus driver from middle school. Her neighborhood best friend who moved and never wrote. They are on one side, whole and alive, and she is here, in the liminal space one finds themself after death comes calling. The mirrors, of course, are not just mirrors. They let in sound and scent and sight. The lingering threads of life float through the connection, calling up memories of the past. Lena passes them all without much thought until she finds something that stops her cold.

Black coffee, pine scented wood cleaner, and downy detergent.

Nana.

Lena wants to see through the mirror, but there is only the thick, black cloth. Nana knows the old ways. That mirrors are portals.

Happiness was her grandparents' country kitchen, Nana placing a plate of olives and mozzarella down on the faded yellow tablecloth. Nana’s soft hands touching the side of Lena’s face as she told her to eat. Be happy.

Lena stands in front of the mirror until the surrounding chill seeps into her lifeless flesh. Lena knows that she is dead, so she’s surprised she can feel cold. Feel anything at all.

It’s a signal. A warning.

She passes in front of another mirror, and this time the black cloth is pulled to the side, allowing a small triangle through which Lena sees a familiar room. Her mother’s face stares back at her. Eyes red and sunken, like she hasn’t slept for days. She flattens her thin skin taut over her prominent cheekbones, then lets them go with a frown. Imperfection was never something Lena’s mother tolerated in anyone’s appearance, especially her own.

Lena presses her face close to her mother’s, but her mother only stares at her own reflection. It feels like a summation of Lena’s entire life. Endless stints of existing but never being seen, punctuated with vicious moments of scrutiny when she wished she could find a trap door behind the bookshelf and escape into a secret world.

The narrow shape of her father sits on the edge of their perfectly made bed. He is hunched, his puffy face staring at nothing. Is he sad because she’s gone or because her death was an embarrassment?

A formal black dress is wrapped tight against her mother’s thin body. Lena watches the familiar sight of her mother smoothing down the elegant chiffon, checking for stray strings or an errant ball of fuzz. Every summer, her mother would bargain that if Lena would just lose weight, she would buy her a new wardrobe, one that would make her the envy of all the kids at school. She would never be bullied again.

She would be happy.

Every fall her mother would look at her with such disappointment. Another year. Another failure.

It always felt ironic that her mother pretended to be her protector from the words of other children when her words were the ones that slid into the hollow spaces between Lena’s ribs like a dagger.

As her parents turn to leave the bedroom, the veil flits shut, severing the connection. Though there is such pain in the remembering, Lena stands at the darkened mirror until her feet go numb, hoping for just one more glimpse.

Crystalline tapestries of ice form on her arms, and when she finally moves, they break off and flake to wet floor. She must keep moving. There’s one mirror she has yet to find. She passes what feels like hundreds until the smell of him makes her smile.

Newports and McDonald’s fries and pot.

Andrew.

He’s sitting on the toy-strewn floor in the upstairs bathroom of his parents’ house. The shower curtain is adorned with the Marvel characters his younger brothers love. He looks wrong in the brightly lit space. A dark shape in chains and black jeans. His head is tucked into his knees, and Lena watches his shoulders heave.

She presses herself against the mirror, wanting to wrap him in her arms like he did all those times for her. He told her he could take her pain away, and he did for a while.

The first time they snorted oxy together, he leaned his huge body back on the basement couch and pulled her with him, telling her she was beautiful as a wave of acceptance crashed over her. She had never felt so seen. Felt so right, just as she was.

He told her slamming it would be even better. He’d done it a few times. He would show her how. Not oxy, though. Heroin would be better. Cheaper.

How could he have known it was fentanyl? He nodded off before her heart stopped, his huge body the only protection from the tainted poison. He held her in his limp arms as she grew cold.

His pain now is a confirmation that he truly loved her. That he misses her. She could stay and watch his grief forever. Let the ice freeze her in place. Would that be so bad?

But Andrew is moving. Restless. He doesn’t look at the mirror as he washes the tears from his scruffy face. There’s a faint click of the light as he leaves, then the deepest darkness.

Standing there, waiting for Andrew to return, feels like the most natural thing in the world. But Lena feels like she’s been pulled from a frozen lake in the dead of winter, and that’s got to be bad. It’s difficult to lift her boots, to keep walking, but she does. Maybe she should go back and find her parents. Or Nana.

Through frosted eyelashes, Lena spies a door at the very end of the hallway. Warm light spills from the edges and dances toward her like an invitation.

Through that door, Lena can leave the House of Mourning, but she does not know what lies on the other side. Or she could stay. It would be so easy to stay, her body already stiff and yearning for rest. But what would she do? Watch her parents grow old and die? Watch Andrew move on?

Before she registers that her heavy feet have taken her there, her hand closes around the brass knob. It doesn’t matter what’s on the other side. She can’t stay here. Can’t haunt this grim, lonely place hoping for a glimpse of her past. That life is gone.

What waits on the other side of the door could be nothing, but it could also be everything. Lena pulls it open and walks through into starlight.

© 2023 Dana Vickerson

Dana Vickerson

Dana Vickerson can be found in the concrete confines of Dallas, though she’s most comfortable deep in the woods where she loves to sit and listen to the symphony of nature. When not crafting buildings, writing stories, or painting weird 3D-printed sculptures, Dana can be found analyzing horror movies with her husband or making elaborate paper dolls for her daughters. She’s a slush reader for Apex Magazine and an active member of HWA and SFWA. Her short fiction appears in Zooscape, Reckoning, Dark Matter Magazine, and many other places. You can find her on Twitter @dmvickerson.