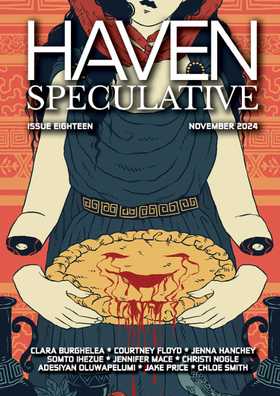

FICTION

The Rooms Behind the Kitchen

by Christi Nogle in Issue Eighteen, November 2024

3695 words

It began at least six months before her end, though of course Rose-Ellen didn't know to frame it in such terms at that time. A little nudge out of her body and to the side, subtle at the start as such dire things often are. She searched for her symptoms and received imperfect terms. Depersonalization, she googled, derealization. Her sensations both were and weren't as described. She was pretty sure it was something else, sharing some features with these known phenomena but ultimately something more.

She cleared her browser history, imagining someone taking those searches as clues to something, in the future. As though anyone would try to unravel the mystery of her life after the fact.

Just that little nudge like a child being pushed out of sleep in the morning, late for school. A gentle push out and to the side, usually the left side, while working, while cooking dinner. Sometimes this was followed by something that felt like weightless hovering.

One night she was making tortillas, straining to hear Geoffrey talk about his day from the living room, and she seemed to double. One part of herself rolled out another ball of dough, and the other part wandered the rooms behind the kitchen, admiring her own keepsakes and clothing with nostalgia, like a person about to go on a long journey. While doing this she could have sworn she was perfectly embodied, the lie of that not discovered until her two parts converged and she found herself back inside her body, feeling uncomfortably warm at the stove. Geoffrey had relocated himself and his phone to the kitchen table. All the tortillas were cooked and softening in their steam, and she stirred some hot chicken to fill them.

It was then that she acknowledged a lingering suspicion: these nudgings-out were precursors to death.

#

She kept this all secret. It seemed a secret thing. Though she was only thirty-two, she knew death was going to happen and that the nudging-out and the hovering were designed to ease her way.

But when? How long?

One morning when she'd stayed home from work, telling herself she was only faking sickness but soon questioning that, she slid out of her body and hovered through the kitchen and beyond it to the bedrooms. There were three—the one she shared with Geoffrey, the one they used for storage, and the guest room, where her mother had stayed a while before her own death in the hospital. This last room was still quite plush and pretty with the shabby chic items her mother had splurged upon after being widowed.

Maybe these bouts of hovering happened to everyone before their death. "Did it happen to you, too?" she asked, but her mother was not here any longer.

It seemed precious, this knowledge or supposition: Not only do the dead keep their secrets after they pass over, but they keep them before that too.

Her mother's wall calendar still hung above the highboy, and as Rose-Ellen approached to look at the kittens on it, the pages below began to change. As though they were layers in a graphic design program, each month being slowly dialed down in opacity. The calendar was open to April—a strange coincidence because it was now April in Rose-Ellen's world, only three years past the date on the calendar. As she hovered before it, April dissolved into May, May to June, June to July, to August, and there on August twenty-first stood a large X. The whole production reminded her of something from an old black-and-white melodrama, except this X was a vibrant Sharpie red. The Sharpie itself lay not far off, on the edge of the highboy, and Rose-Ellen wondered who had made that mark, and when.

When she next saw her body, lying on its side on the living room sofa (she did not remember lying down), Geoffrey sat there with it, stroking its hip. Already evening, then.

She had not faked illness; she had been ill, not with the fever or respiratory problems she'd implied when calling in, not with anything one could pinpoint, but with the knowledge of impending death. Something like dizziness, shakiness, but not in the body at all.

As Geoffrey stood and began to pad around in search of something to make for dinner, the body stirred. Rose-Ellen stayed fixed in the kitchen doorway, curious. How could it move so well without her?

"You home?" the body called weakly, though Geoffrey had been inordinately quiet.

He hurried into the living room, passing right through Rose-Ellen in the doorway, and asked, "How you feeling?"

"Yeah, I don't know," the body said. It asked for the time, offered to help with dinner. A decision was made to order out, and soon it was eating more noodles and crab rangoon than a sick person ought to be able to manage. Rose-Ellen tasted the salt and fat and sweetness but had no particular urge to return to the body and experience those familiar textures in her mouth. Geoffrey cleared away the trash and leftovers, and the couple settled down to watch a movie. The room darkened.

At some moment she could not put her finger on later, Rose-Ellen returned to herself, or rather, her self returned to her body, uncomfortably humid in a sick-smelling T-shirt and couch blanket. Geoffrey snored softly beside her, and she eased out so she wouldn't wake him. She moved toward the rooms behind the kitchen, turning briefly to affirm that her side of the couch lay empty, that she had in fact brought her body with her this time.

She moved through her bedroom and the storage room, feeling that she'd gone to look for something. The objects and the spaces before her had drained of significance, all clearly not what she had been looking for. She cracked the door to the guest room, bracing to see her mother. This was not new; she'd been doing this ever since the woman died—several times a day at the start, then less and less as the years unrolled. Though the death had taken place in a hospital room, though Rose-Ellen was as unspiritual and irreligious as they come, she always tensed to see the ghost here, unsure whether the sighting would bring joy, relief, fear, or something wholly unexpected.

She sometimes rushed past the door without cracking it, too afraid to look.

"Are you here?" she called softly now. "Did this happen to you, too?"

There was, of course, no answer, and Rose-Ellen went about readying for bed.

#

Was the death already inside her body, cancer or something, or was it some accident ahead of her in time? Her disquiet seemed not in the body at all—but maybe that feeling would be the cause, she mused, maybe the uneasiness would cause her to make a wrong move on a stairway, in the car. She'd decided the feeling was soul-queasiness, simple dread. So far it had not affected her driving, her balance, certainly not her appetite—though she did notice herself edging out more often around mealtimes. Food was no longer of interest to her. It had been that way with her mother at the end, too.

April, May, and June went by, warm and vivid. The body went on eating, went on exercising, going to work. She had moments thinking she ought to quit her job, to make the most of these last few months, but there were so many reasons not to. She'd laid them all out in her mind and not on paper, as she usually would have done. First, the missing income would put Geoffrey in a bind; second, it would raise his suspicions. He would want to talk about things, and if they talked very much, he would take her to the doctor. Third, what would she do, to make the most of her time? She wasn't the type to run off on vacation alone, even if there were plenty of funds. Travel held no interest. She had no life's project to hurry up and finish. Lying around on the patio furniture reading and watching television from the couch was about the best she could imagine, and surely there were enough hours for these activities already, even more so with the lengthened days, and so she kept going to work. She even dressed up a little nicer and made efforts to be funny and charming, thinking to leave her colleagues with better memories. She had not always had the best attitude around people.

Soon she began moving out of her body at the office. With a spreadsheet before her, a series of calls to make, she would hover into other rooms, listening for mentions of herself. There were many items of gossip and painful personal matters to hear, but they were about other people. No one spoke of her. Well, one man did say she'd been looking hot lately, wondered if she was thinking of divorce, but that wasn't the type of thing she'd been listening for. She'd been listening for something about her character, some defining sentiment that would let her know herself. How she was perceived, if she mattered.

No answer came.

After a time, she wandered farther, into other offices filled with people she'd glimpsed but never known, and finally down to street level, exploring little cafes and shops or the large, shady park, places she had briefly visited and never lingered over as well as places still untouched.

There was no sense of urgency to any of it, and at night sometimes before falling asleep she would tell Geoffrey how happy she'd been recently. Calm, contented, whole. She wasn't only thinking of leaving him with nice memories, though that was something; she was mostly expressing how she felt. How she wanted to feel.

Expression gained importance. As August twenty-first came closer, she wished to express to him something of what she had been experiencing, just enough for a balm, later. Nothing would come. She could not move her mouth to say anything of substance and eventually stopped trying.

#

As the days turned scorching hot, intermittent bursts of desperation broke through her constant state of calm and dread. She woke Geoffrey once in the night, twice, screaming. He said she'd been speaking, too, though he had not understood the words.

Reading now exhausted her, same with television. The one little gesture she had made toward her death was a reckless spree on annuals—petunias, verbena, little African daisies in pastel colors, coleus and such. She'd nestled them in hanging baskets and had gone to them in the mornings before her commute, in the evenings before Geoffrey came home.

Her mother had loved annuals. Rose-Ellen never thought them worth the expense, but having bought them she cherished them as much as she could, picking off insects and wasted petals. Watered them, fertilized. By July they were ailing despite it all. She took pity and sent them to their end in the composter before the last blooms could open. She cried and washed her face before Geoffrey saw.

He never remarked on the disappeared planters. Did he not notice, or was he avoiding the mention of them? Did she seem that fragile now?

There was no way to communicate anything real to him. She had tried scores of times. Her mouth would move to talk about dinner and weekend plans and all the banal things, but it could not say You ought to feel free to find someone, soon if you want or I've been leaving my body sometimes. I think everyone does it near the end.

The death was inevitable—she had known that from the finality of that red X on August twenty-first's square—but acceptance is not as easy as it seems. Of course she had thought about finding help at her doctor's office, the emergency room, other random medical facilities she passed on the way to work. She had also thought about therapy, church, a support group. Her mouth would not move, fingers would not press in the numbers on her phone. Her hands would not turn the steering wheel, her foot would not move for the brake pedal, and soon her eyes would not even focus on the things they wanted to see.

#

Rose-Ellen found herself at the kitchen desk typing, late at night, part of a performance review for a woman she'd been hoping might replace her at work. She'd already done a copious amount of writing, much more than she would ever need, and yet she could not stop listing more and more observations of this woman's competence and attention to detail.

She thought she was fully engaged, but after a time she began to feel sleepy and soon her vision went black, as it sometimes did when she fell asleep reading before bed, yet the writing kept happening without her. She could hear it, feel the impacts on her fingertips. Something about this made her suddenly furious. How had she lost control to this extent?

Desperate to wrestle back some of her autonomy, she strained. Like lifting a heavy weight, like struggling on the last few minutes on the step machine at the gym, strained until she was the one typing, almost one hundred percent in control:

August twenty-first, august twenty-first, august twenty-first, it's the day I die the day you die it's the day you die and you have been half-dead for months now rose-ellen don't you feel it?

A strong convulsion gripped her and she seemed to shrink to a point before expanding outward, pushing herself away from the desk on the rolling chair, knocking the chair on its back, stumbling back but not falling. She wasn't the one to take any of those actions. She'd not been nudged-out this time but swiftly expelled like a long-held breath, and now she turned. The body took one long gasp and then it whispered, "Who's there? Who's there?"

It could not see Rose-Ellen facing it. Its eyes roved back and forth like someone faking blindness.

#

Rose-Ellen lingered in her mother's room late in the night. She had been agitated and came here to avoid waking Geoffrey with another nightmare. She curled on the bed in the dark, thinking of nothing.

The door cracked, and someone gasped. Rose-Ellen gasped, too. When the big overhead light flicked on, she was the one in the doorway, just like that, and no one was curled on the bed.

The next day, Saturday, they lingered over late coffee and toast on the deck. Soon it would be too hot to be outside even in the mornings. Geoffrey recalled to her a dream of fishing from a massive aquarium, and when he finished, she described her own dream:

Her spirit had left her body and gone to her mother's room, and her body had come looking for her without knowing what it was doing. It cracked the door, anticipating a ghost, and found one curled on the bed. Meanwhile, as she lay there on the bed, she had been sure it was her mother coming, knew she would finally see this ghost she had been looking for and braced to see.

Rose-Ellen was amazed she'd been able to say something.

"In fact, I was all of them—the me in the doorway, the me on the bed, the ghost I was hoping to see—I was all of them. I can't explain."

I was you, too, I was the bed, everything. The door.

She couldn't say all of it.

Geoffrey never read a paper. He did not lower any paper and make intense eye contact over it. The effect was the same, though. She'd pulled his attention from food and drink and phone. She saw him debating what to think of this, what to say.

"I know you're always missing her," was what he settled on.

Rose-Ellen nodded.

#

Two weeks left. Rose-Ellen cleared away the things that were only hers, the things that were meaningless now. In the night she used the backyard fire pit to burn the things she thought might burden him the most—pictures of her aunts and uncles, grandparents and parents, all dead, the clothes too threadbare to donate. Less flammable things she sneaked into the garbage one at a time, hiding them under packaging waste and plastic shopping bags.

Over the years she had written poems, sometimes little essays and short stories. She browsed through these in a single afternoon, collected the few most complete and accessible of them in a folder she titled "creative writing," and deleted the rest. She wrote all her passwords out clearly on a sheet of paper and left it folded in her desk drawer. After some incognito browsing she told herself she had no need for a will, as Geoffrey really was her only tie to the world. He still had family. He would have a new partner someday.

If she had thought it necessary, Rose-Ellen had no doubt the body would have written out the thing and driven it to a notary with no complaint. She would have been able to. It wasn't that she'd taken control of the body; it was that the body had the same thoughts as she did. They were separate but working in agreement.

It was so easy to settle her affairs, all done within a week so that in her final days all she had to do was sit in the air conditioning. At work, at home, she sat quietly in the cool trying to believe there was no separation between her selves. She resisted all urges to split, resisted her mother's bedroom door, too, until a night very close to her last when she remembered the calendar. She would have to take it down so that Geoffrey couldn't see the X.

At the door, she did not brace for anything. She opened it quickly.

Rose-Ellen was in the midst of a different time. Sunlight came in strong and her mother was in the bed, looking not healthy, but perfectly coherent and cheerful.

"Oh, breakfast?" her mother said. The TV emitted the chirpy banter of a game show. Nothing in the room surprised Rose-Ellen as much as her own self did. Her arms, feeling stronger than they had, held a tray heavy with eggs, toast, juice, coffee. Her arms wore the faded brown fleece of a top she'd burned weeks ago.

She was shaky inside, but her body moved steadily, under its own control. It waited for her mother to scoot back, then settled the tray on the rolling table.

"Sit with me?" said her mother, and Rose-Ellen settled on the flowered chair beside the bed. Such a beautiful pattern. The chair had been in the room all this time but she had not taken it in. Now she traced the flowers with her finger.

They watched a nervous woman spin a massive wheel.

"I thought you might like to wait here while it happens," said her mother, dipping toast into runny egg.

"While what happens?" said Rose-Ellen, but her mother gestured to her mouth, too full to talk.

The door creaked, and Rose-Ellen startled. "Geoffrey?" she called, but the door only stayed like that, just-cracked. She rose and peered through the crack, but there was nothing. The hallway was entirely dark.

She seated herself again. "Where's your calendar?" she said. It no longer hung above the highboy.

Her mother had just taken another huge bite. She rolled her eyes and then held a finger in the air—just a minute—and reached for the remote. She hit the channel button a few times and passed the remote to Rose-Ellen.

There, in black and white, was this very room. A grainy nightvision shot. The door cracked and stayed cracked a moment until a woman swept inside. It was Rose-Ellen, looking gaunt. She stood in front of the calendar for a moment, then took it down and left the room.

The oversized thumb tack still sat there on the highboy, glinting in sunlight, proof of the event.

Something was wrong now. The TV showed another night-time view, the backyard. Rose-Ellen squirted lighter fluid over the calendar and lit it, but all the time, the sounds from the game show broadcasted over the images.

Her mother stifled a burp. She'd all but finished the food.

"You said to stay in here while it happened. What did you mean?"

But her mother was back to being a memory. A recording. Something about the old woman's eyes told Rose-Ellen her mother was trapped inside of herself, straining and failing to communicate.

"This lady's going to win the whole thing," her mother said, gesturing at the TV. The crowd cheered, but on the screen, Rose-Ellen's death played out. It was a car accident after all, caused by something falling out of the back of a pickup ahead of her on the freeway. She was glad to get to see it from this distance and know that it was not her fault, that there was not a thing she could have done differently, that no one else had been hurt.

Truly ideal.

Rose-Ellen turned to her mother to say she was grateful, but this body she inhabited was back to being a memory too. It could only say, "We've got to go in for your tests this afternoon."

"Pack me some puzzle books and things. I bet they don't let me back home," her mother said.

This was true, and her mother must have known it for a long while, and yet Rose-Ellen's mouth assured her, "Just some tests. You'll be feeling great soon." She controlled this ghost-body not one bit more than she had the corporeal one, and with this knowledge came a surge of relief.

Their eyes seemed to communicate, there for a while, but as the body began packing for the hospital visit, Rose-Ellen slipped away from it to wander through the other bedrooms, dark again. So many rooms now. Geoffrey slept all alone, and the house unfolded, infinitely complex but silent. Silent, neat and clean, ready for someone new.

© 2024 Christi Nogle

Christi Nogle

Christi Nogle is the author of the Shirley Jackson Award nominated and Bram Stoker Award® winning first novel Beulah as well as three short fiction collections: The Best of Our Past, the Worst of Our Future; Promise: A Collection of Weird Science Fiction; and One Eye Opened in That Other Place.

Her work has also appeared in over fifty publications including Strange Horizons, Apex, PseudoPod, and Three-Lobed Burning Eye.

She is co-editor with Willow Dawn Becker of the Stoker-nominated anthology Mother: Tales of Love and Terror (Weird Little Worlds) and co-editor with Ai Jiang of Wilted Pages: An Anthology of Dark Academia (Shortwave Publishing).

Follow her at https://christinogle.com and on across social media under the username christinogle.