FICTION

The Ways the Woods May Answer

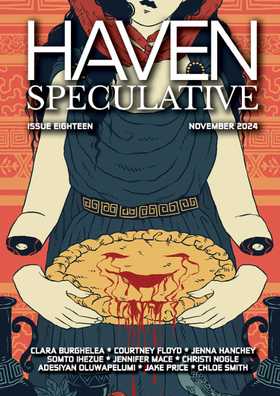

by Jennifer Mace in Issue Eighteen, November 2024

1549 words

They would not bury her in consecrated ground. Her life was all the wrong forms of holy.

She walked barefoot through Beltane fields and knew all the herbs of the deep woods; her hands were the first touch infants knew in life, and those who had only the cold press on the eyelids of corpses, the swipe of water over supplicant brows, were jealous of that bloody strength.

No matter. Your beloved did not belong below stone or ringed by paltry yew.

#

You plant the seed in a distant clearing among bracken and fallen mast. It is the first full moon after harvest, and the ground is still supple with rain.

Six feet is the rule when wolves and starveling foxes abound, but no sprout can stretch six feet to breathe. In compromise, then, you dig a pauper's grave: two feet deep by one across, wide as the blade of your shovel. The wet yielding weight of the seed sits tight against your breast as you dig, listening to the beating of your heart.

This is not your expertise: a spinster has no call to act the witch.

But the witch is dead and two weeks aground, and there are things which must be done, no matter how messy or inadequate the hands.

You lay her down into the calm hollow of the earth, below the reach of wind or creature. The splinters of her coffin sit sharp beneath your nails, smearing your blood after hers; you gentle the soil back into place. None must know what dwells there.

None but you.

#

After that, you wait.

Moons wax and wane and the stars circle ponderously in the heavens. Your wrist-bones grow stiff with approaching rains, then falter in the cold grip of snowfall.

Each month, you visit. Press gifts of your body into the soil, spun wool and linen, carved figures, hair and fingernails and hoarded treasures of blood. You are teacher and mother both, chipping away the frozen earth to feed the thing below.

This is what it means, you tell it. This is what it means to be a woman, a wife, a witch. Tears and blood and blisters; the wheezing rattle of lungs; the paranoid ways you startle at every broken-twig sound. Everything you are, you teach.

The earth swells and settles. The seed shrinks and bursts and sprouts. First frost arrests its development, and panic dwells unasked in a hollow in your chest, pressing down and down for months. You lay soft mosses about the shoot; you blanket it with snow; you trap the warmth below.

You do not pray. Gods which dwell in cold stone houses have no part in this holy writ of soil.

#

Spring comes, and with it, hope: the sapling grows and sprouts leaves.

You palpate the swollen dirt around the shoot like a midwife pressing another woman's belly—here a foot, there a shoulder, or perhaps just rocks and wishing—and bite down on desperation.

There is dirt beneath your fingernails, dirt ground indelibly into the weave of your skirts, your skin, dirt everywhere lanolin once stained. You have wrought of your grief a choice, in this unbreathing mass beneath the earth, brought on yourself a transformation. The forest wraps its silence around you like a chrysalis, and you do not know where this will end.

Moonrise finds you sleeping, wrapped bodily around the faltering new growth.

Across the wild garlic and curl-clawed ferns, a fox waits, one paw suspended, its breath a smoke billow over frosted ground. You watch one another, wife and wildlife, as night sings through the budding branches overhead.

Wrapped in the curve between belly and breast, the tree has grown. The trunk is as wide, now, as the wrist of a child, and its branches stretch as tall. You swallow, overcome, and press your palms against rough new bark.

The fox, forgotten, sets paw to earth. Bows. Leaves.

#

After that, you barely step away.

You mean to. You should. You must. She would have hated this for you: hated to watch you lose your place amongst those which you once loved.

But to walk between the houses of those who have so easily forgotten her footsteps—to wash and card and spin their wool, to speak their politenesses, to clothe them—is more than you can bear, when she grows so cold beneath the earth.

And so, piece by quiet piece, you step away.

There are songs in the deep woods which now hum inside your bones. You begin to understand the things she tried to teach you, and it is a bitter ache to walk barefoot through bramble without her by your side, watching the flight of birds and the silent stir of centipedes.

You push through. You must. The seed which you planted is growing. And it hungers.

#

Spring equinox; five feet tall. Beltane; eight feet. By the first new moon of the harvest its crown stretches taller than you can reach with a besom. Branches rattle at your approach, even in the dead air of summer. You pat the trunk, as broad now as your waist; run careful fingers through the dagger-sharp foliage.

You feed it like a carrion creature, a crow. It outgrew beetles and centipedes months ago, grew tired of voles and of finches. One night, when you returned late from thieving netting from your own home, you watched it spear a squirrel. The blood stained black all across the lower branches. No animal has dared touch it since.

Except for you.

This is not the woman you loved. You have done an evil thing.

You knew that, though, from the moment you set dagger to breast and hammered home, broke ribs. Felt the sweet stench of her decay coat the back of your throat. Saw her skin, the way it sloughed from flesh. Your true love turned to rot.

You have come too far to balk at blood.

Three rabbits hang from your belt. Traps are a logical exertion of fiber against flesh, and your fingers weave them fluently now. You feed the corpses, one by one, to the deep angled hollows between roots. In the faint satiated crunching which ensues, you steal a little closer. Lay cheek to dirt. Listen. Listen harder.

You think you hear her breathing.

#

The earth splits in early autumn.

A wailing cry wrenches you up from sleep, shakes you free of the leaves which have fallen in the night. You cross the clearing on your knees. A supplicant.

The earth heaves. Cracks have formed between the roots; they gape and fall back closed, like a bird too weak to break shell. Frantic, you force your fingers into the soil, tear and tear and tear at it. No tame, plowed crumble of field-dirt, this; you rip through the binding filaments of fungi, of weeds, and break open your nails on the thorned roots of the tree you have wrought.

It fights you.

Moonlit eyes glint from the edges of the clearing: owls and bobcats and wild pigs; a badger. The fox has brought its kits to bear witness.

You bleed. The razor-sharp leaves flay first the cloth from your back, then the skin. Your palms tear bloody. The pain comes in waves, like the ocean. The bobcat edges closer.

But under the soil: something pale. Moving. Your breath comes in tearing gasps as you brush enough dirt away to see—

There is a cough. A whimper. And then: a quavering, desperate wail.

No, you say, a hoarse whisper, horror chill as the grave. No, no no—

The baby's cry is louder.

For an eternal, depthless moment, you think: Bury it. You have dug too soon, plucked the wrong harvest. If you just—just push the dirt, tamp it down, down, until the crying stops, until—

Try again. You can try again, you must—

The tree has fallen still. Slowly at first, then all at once, the leaves begin to drop. The trunk creaks, shudders. Bark splits. Sap spills dark as blood.

It is instinct. You curl yourself over the infant, yank it up from the dark chill soil, from the grave where you planted your wife's dead heart all those months ago, and press it into the curve of your body even as you weep, even as the leaves tear into your skin.

You have paid a price, and paid it in full, for a wish as dark as the hollow between your knees, but you realize now, too late:

The witch does not control the ways the woods may answer.

#

The last leaf falls. The tree splinters and blackens to a stump. In the eventual silence, you think you feel it: the weight of your wife's gaze, warm against the back of your neck.

You jerk around, gasping at the pain, but there's no one there. Only the moon-glint eyes of the fox, wary in the undergrowth.

It meets your gaze for a heartbeat. Nods. Scruffs its kit and flees.

In your arms, the baby grizzles.

Beneath the waxing moon, dirt-clad and wrung empty by pain, you bow your head, and laugh and laugh and laugh.

#

In the heart of the deep woods, there lives a witch.

She is teaching her daughter how to spin.

© 2024 Jennifer Mace

Jennifer Mace

Jennifer Mace is a queer Brit who roams the Pacific Northwest in search of tea and interesting plant life. A four-time Hugo-finalist podcaster for her work with Be The Serpent, her short fiction and poetry may be found in magazines such as Baffling, Flash Fiction Online, and Uncanny Magazine. Find her other works online at www.englishmace.com.