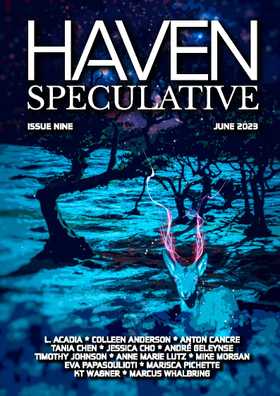

FICTION

To Call My Own

by Jessica Cho in Issue Nine, June 2023

I was nineteen when the first holes appeared, just on the cusp between thinking I knew everything and realising I knew nothing. Walking home from work with Mellie, we turned onto Chestnut Street and found our path blocked by a crowd of people.

“Sinkholes,” a woman was saying. “Like the ones in Guatemala.”

“Nah.” This from a man with a small child at his side, gripping his hand tightly. “Burrows. We used to see this kinda thing when I worked out west. Them critters’ll burrow the ground right out from under you.”

“It’s the damn city, that’s what,” said an older man. Permanent frown lines creased his forehead. “Tearing up roads with construction and digging gas lines and never telling anyone when or where. Irresponsible is what it is.”

We were finally able to push our way through the gathered ring of people to see what they were all looking at.

It was a hole. A hole in the ground maybe three feet deep and roughly egg shaped. If I jumped in, I could touch both edges with my arms outstretched. The sides were smooth dirt, with no signs of any loose soil within, as if something had simply scooped out a giant handful of earth and carted it off. Mellie and I shared a look.

“Definitely sinkholes. My sister sent me pictures from when she went to build houses in Guatemala. They just showed up out of nowhere. Big ones. They can swallow whole villages.”

Mellie shrugged at me. “Probably just some kids playing around,” she said, but not too loudly. “Remember when we used to dig pit traps in your mom’s garden? We thought we were hunting tigers.”

I remembered. Our games came to an abrupt end when Mr. Goodrich stepped in one and broke his ankle.

But this wasn’t some rough-dug product of a child’s imagination. The sides were even and the bottom level, though I could see the dirt inside was still soft. I sided with the sinkhole woman.

“In Ashland?” Mellie snorted. “May as well be tiger traps.”

#

Over the next few weeks, more and more of the holes appeared. They remained in the outskirts at first, marring pastures and old country roads, occasionally showing up in cornfields, like tiny crop circles. Then they started appearing in more populated areas, dotting suburbs and city centers alike. People wrote angry letters to the City Council and the Department of Public Works, demanding answers and repairs, but it soon became apparent that this was bigger than Ashland, bigger than Michigan. It was happening all over the world.

“Mole-people,” Mellie said one day, watching the news from our ratty couch. Aerial cameras panned over acres of pastureland, pockmarked with the now familiar depressions. A honeycomb of dirt that made my hands itch and my bones tingle with discomfort.

“What?” I asked, half distracted. The folding table that served as our dining set was strewn with bills. Mellie had lost her job earlier in the month, while I’d kept mine by the slick of my teeth, but at half the hours. I’ll make it work, I’d told her.

“Mole-people,” she repeated. Her eyes were fixed on the screen, but I could see the tiniest curve to the corner of her mouth. “They’ve been digging for generations, building whole civilisations beneath us. We’ve gone too far, done too much damage to the planet and they’re going to put an end to it. This is just the start.”

Nations spat and pointed fingers, throwing around accusations of sabotage and illegal surveillance. On screen, people were gesturing and speaking rapid-fire in a language I didn’t know—a new hole had appeared beneath an old wine cellar with a packed earth floor. Thousands upon thousands of dollars’ worth of bottles damaged or disappeared.

Mellie shot me a full smile, the first I’d seen from her in days. “Mole-people get thirsty, too.”

That night, we lay side by side on the living room carpet with our ears pressed to the ground, listening for sounds of the mole-people digging beneath the earth. The building groaned its tired complaints as we breathed in the faint smell of mildew and stale cigarette smoke. Neither of us cared in that moment that our apartment was on the third floor.

#

After a month, the first holes began to fill.

It went unnoticed at first, but once you saw it, it was impossible to miss. One patch of smooth earth among a dug-out row, its very presence an absence. Like a missing tooth that’s since been replaced, but you can’t stop pressing your tongue to the spot where it used to not be.

I’d unplugged the TV after weeks of enduring the same ubiquitous images of wounded earth, but the news still crept in. Now it was focused on a new phenomenon: the people who were climbing in.

No one knew who went first. The news reports talked of a cult, others of conspiracy, but all anyone knew for sure was one to a person and a person to each. Someone would curl up neatly in the dirt and the next day the earth would be smoothed over. Even when dug up immediately, nothing of the buried was ever found.

“I bet it’s peaceful,” Mellie said. It’d been weeks, and she still hadn’t been able to find a new job. I’ll make it work.

Above us, the sound of stomping feet, shouts and raised voices. Breaking glass like shards of anger. We tried to ignore the way the thin walls of our apartment shook and shivered, like it was afraid.

“They look cozy,” I allowed. Beside me, the stack of bills on the table leaned precariously to the side, as if even they were tired.

“Yeah.” Mellie cupped her hands together in front of her and frowned, staring into them as if trying to figure out how to fit the whole of her body into the space she had created. I reached over to tuck a strand of hair behind her ear, wondering when the circles beneath her eyes had grown so dark.

“Don’t worry,” I told her. “I’ll make it work.”

“I know,” she said, not looking up from her cupped palms. “I know you will. That’s just...that’s what you do.”

Three days later, she was gone.

The note she left on the folding table was neatly written on smooth paper. Whatever she’d been thinking, however she’d been feeling, her hand was steady. That might have been what hurt the most.

I guess you probably know where I’ve gone. I’m sorry. I feel like I spend all my time just trying to carve out a place for myself without knowing if it’ll ever come to anything. I don’t know what happens to anyone in those holes, but I do know that the one I choose will be mine and no one else’s. Who knows, maybe I’ll go live with the mole-people. I bet they’ve got space for me.

This isn’t your fault, even if I know you won’t believe me. You never made me feel like I was a burden, but I can’t keep taking up room in a space that’s barely even yours.

This is what I want. I hope you find something to look for, too.

Love, Mellie

#

Three more weeks went by. The holes began to fade from public fervour, news channels returned to sports and weather and politics. The holes didn’t all vanish, but we absorbed them into our everyday lives. Every now and then, neighbours, friends, family would quietly disappear and new patches of smooth earth would show up in the morning. We grieved. We moved on. They weren’t dead, not really, but we had to treat them as if they were.

There were still theories, of course, ever growing. Aliens. Teleportation. Solar flares. One popular speculation among the crunchy granola crowd was that the earth was opening up to take us back into herself. I thought of the sinkhole woman and her sister in Guatemala.

I was lying on the kitchen floor when I felt it. It was oppressively hot, and I was trying to absorb some of the coolness from the linoleum in the sweltering afternoon. Mellie leaving had given me a little financial breathing room—a fact I hated almost as much as I was thankful—but not enough to afford the electric to run the AC.

Beneath the sweat beading on my skin, I felt something shift inside my chest, small and subtle. It was as if suddenly a strand of spiderweb was connected to my heart and I could feel every tug and vibration of whatever was on the other end.

I followed the pull outside and was immediately drawn to the field across the street from my apartment complex, still riddled with holes in the dirt between the rusty playground equipment. The vibrations grew stronger, pinging from the ground as if every hole was a strand.

No.

As if every filled space was a strand.

I picked a hole at random. It didn’t matter; at this point every heartbeat thrummed and my skin felt tight, like it was too small for my body. When I lowered myself in, it was like slipping into a warm bath, like taking off my shoes after a long day, like sliding my hand into a friend’s.

The cool earth embraced me on all sides, save for the blue above my head. It felt good. More comfortable than the apartment ever had, even when Mellie had been there. I felt the tension leave my shoulders as I curled up in the bottom, breathing in the loamy air.

I thought about sinkholes and government conspiracies. I thought about God and aliens and burrowing creatures the size of Volkswagens. I thought about mole-people. I thought about Mellie, trying so hard to carve out a space that could be just hers in a world reluctant to give up anything.

I lay back, eyes on the clear blue sky, and I waited for the emptiness to fill.

© 2023 Jessica Cho

Jessica Cho

Jessica is a Rhysling Award winning writer of SFF short fiction and poetry. Born in Korea, they currently reside in New England where they balance their aversion to cold with the inability to live anywhere without snow. Previous work has appeared in Fantasy Magazine, khōréō, Fireside Fiction, Daily Science Fiction and elsewhere. They can be found online at semiwellversed.wordpress.com.